This is a compilation of the designer diary entries Jamey posts on the Charterstone Facebook group. They are listed here in chronological order, with the most recent entry at the top (so if you’re just now finding this, it’ll make more sense if you start from the bottom).

***

November 15

What did I learn from my previous published designs that I applied to Charterstone?

Someone posed this question in the comments a few weeks ago, and I’ve been looking forward to writing about it. Each of my designs is informed and influenced not just by other games, pop culture, and behavioral psychology, but also by the designs that preceded it. I’m proud of those designs, though I know they’re not perfect.

VITICULTURE: One of the big things I learned from Viticulture is the importance of flow. I didn’t fully realize that when I designed Viticulture. I like when short turns flow naturally, one after the other, without the artificial boundaries of rounds and phases. So even though there were early iterations of Charterstone that used rounds, they weren’t flowing the way I wanted, so I got rid of them. Now players simply take short turns, one after another, until the game ends.

Another aspect of Viticulture is that random card draws can be frustrating for players. Now, the game is built around this concept—Viticulture makes it easy to draw a lot of cards, and you’re supposed to make tactical and strategic decisions to optimize the cards you draw. Also, the visitor cards have small text on them that I wouldn’t want to ask players to read from across the table if selecting from a card river. However, I didn’t want to impose this frustration upon players in Charterstone, especially since card draws are not nearly as abundant as in Viticulture. So in Charterstone there are always 5 face-up advancement cards you can choose from, and they’re designed with big icons that you can easily see from across the table.

I want to mention something positive for each of these too. Something that I think works really well in Viticulture is the satisfaction of working towards a big payoff at the end of the game. Charterstone has a lot of ways to get points throughout the game, but there are certain mechanisms like the reputation track, guideposts, objectives, etc that often pay off late based on a well-executed plan. I like that.

EUPHORIA: My biggest regret in Euphoria is that it’s quite difficult to teach or learn, especially for a game that isn’t all that complex. The board makes the game look MUCH harder than it really is, and there are tons of interconnected systems that prevent you from explaining just one thing at a time. In this way, learnability became a top priority for Charterstone. I wanted players to be able to sit down and just start taking turns. In a way, the entire Charterstone unlocking system is built around this goal.

Another thing in Euphoria that doesn’t work particularly well is that near the end of the game, you can almost always see who the winner will be a few turns in advance, and there’s nothing you can do about it. It results in a lack of drama. Not that the end of a game always needs to be some big surprise, but it shouldn’t just fizzle out. In Charterstone, it is certainly possible for a player to pull ahead. But there’s often a lot of back-and-forth throughout the game, and the reputation track and guideposts—many of which have you comparing yourself to other players—can create some nice end-game tension.

My favorite thing about Euphoria is the worker-bumping system, and I copied it almost exactly for Charterstone. The idea is that in a game without rounds, you need to occasionally use a turn to retrieve your workers. You can optimize this by “bumping” your worker off an action back to your supply (or positioning your worker so someone else bumps it). It’s a nice level of positive player interaction, even though you want to avoid bumping opponents if possible. I really like the flow and flexibility of the bumping system, so I used it again in Charterstone.

SCYTHE: One of the most common complaints about Scythe is that the end-game trigger is “sudden.” While experienced players know to keep an eye on their opponents, it can be frustrating for new players to suddenly be informed that the game is over. I address this with the resolution tiles in The Wind Gambit. In Charterstone, there’s a very visible progress track that conveys how close you are to the end of the game. Players control through their actions how quickly the progress track advances, and it often really speeds up at the end of the game. Also, the game ensures that all players get an equal number of turns.

Balance is another issue in Scythe. Despite the 1000+ blind playtests, we still ended up with a few factions that are slightly better on average than the other factions. I really wanted asymmetry in Charterstone, but charter balance was on my mind throughout the design process. There were certain times in development when I realized that a player’s charter mattered too much, which usually resulted in me cutting the associated rule. I also tried to give players a reason to try out different player powers rather than using the same one, just in case one ended up being better than another.

My favorite thing about Scythe is how the engine-building system constantly rewards players. I like to feel rewarded in games, and within each session, I like to feel like I ended up more powerful than I started out. Charterstone was in interesting challenge in this way, because I needed to have engine building within each game and across multiple games. Giving players a limit as to what they could keep, combined with glory bonuses earned from cumulative points, helped strike that balance.

If you have any thoughts/questions about this topic, feel free to share them in the comments!

In just 2 days we’ll have the Australia/NZ/Asia release of Charterstone, followed by the December 12 release everywhere else. Also, there will be no design diary next Wednesday due to some family time for Thanksgiving, but please know how truly grateful I am that you’ve been a part of this journey over the last 6 months. Thank you for your patience, and I can’t wait to get Charterstone on your table.

***

November 8

I completed my 6-player, 12-game Charterstone campaign on Saturday afternoon.

I completed my 6-player, 12-game Charterstone campaign on Saturday afternoon.

Even though I designed the game, playing with the real components instead of scissors, tape, and homemade cards is a completely different experience. That’s one of the reasons why I had my manufacturer send me a fancy prototype back in the spring, as I wanted to simulate the first few games when players are learning a lot of rules from the cards. It was after that simulation that I added a reminder on every card as to what the players should do next (instead of leaving them with general instructions to take the next card from the Index).

We played the campaign in 6 sessions spread over 8 weeks. Each 3-hour session included a meal and 2 games of Charterstone. Everyone except 1 player won at least 1 game throughout the campaign, and I wasn’t the overall winner.

In fact, I was really pleased with how the final scoring worked out in reality. I won’t spoil how it works, though players know all of the end-of-campaign scoring categories by the end of the first game. There are different facets to the categories that give all players a chance at winning even if they didn’t win any individual sessions (but it still rewards players who go for a win each game).

One thing I was curious about was the sense of pride and ownership each player would have over their charter, given that you can place workers on any building in any charter. Again, we tested this, but it’s different when you have the final product. I was REALLY happy with how this turned out. Players frequently said things like, “Hey, don’t you want to use my [building name]? Come on over to my charter!” Also, just because you’re the one who constructed buildings in your charter and you sit near your charter, you know it better than any other charter. I had a strong attachment to my charter, yet I still felt connected to the overall village. This—plus the naming of many cards in the games—really seemed to instill a sense of pride and ownership in what we were building and using.

I was happy with the reactions to the twists and turns, and I was pleased that each scenario retained the core feel of the game while pushing players in different directions. Also, even with 6 players, we were still unlocking in-game content during Game 12—there’s a lot of stuff to unlock.

I’m sure you’re wondering if there’s anything I would change now that I’ve played through a full campaign with the final version of the game. There are certainly some minor things I wish I had caught or explained better in the rules, but they’re in the FAQ. I’d say the biggest thing is that Game 11 dragged a bit for us. It wasn’t even related to the special rules for that game—I think it’s mostly that a big part of what moves the game forward is players unlocking and building, and by that point in our 6-player game there wasn’t much more to unlock or build (there is an independent way for the game to move forward, fortunately). Due to a special rule, Game 12 doesn’t have this issue at all.

I can’t really talk about the other stuff with which I was pleasantly pleased without going into spoilers, so I’ll save that discussion for a month or so after the game is released.

Is there anything you’d like me to share with you now that I’ve completed a campaign of the published game?

***

November 1

Today’s Charterstone post will be short, as it’s mostly a rehash of an announcement I just sent out in our monthly newsletter.

It has become an annual tradition for us to host a charity auction for a special product that brings attention to some of my favorite tabletop content creators and supports the charities they’re passionate about. This year the auction is particularly special because we’re going to match the winning bid for EVERY auction to double the charitable gift.

This year we’re auctioning off 10 signed advance copies of Charterstone, each enhanced by the recharge pack, Meeplesource meeples, and the Top Shelf Gamer realistic resources.

Now, I want to be clear that while this auction is a way to get an early copy of Charterstone (I had them air freighted from China, and they’re currently sitting behind me in my office), it is not a *cost effective* way of getting Charterstone. But you may look at the auction and realize that you’re passionate about some of the charities that these content creators support, and it may feel good for you to bit, especially knowing that Stonemaier Games is going to match the bid dollar to dollar to double the charitable gift (if you bid $200, the total we’ll send to the charity is $400).

Also, even if you don’t want to bid, it’s a neat way to learn about some of the content creators (bloggers, podcasters, and video bloggers) whom I admire, follow, and recommend.

The auction is live here and ends in a few days. Thanks!

***

October 25

It’s been a busy week for Charterstone! Last Wednesday I featured most of the advance reviews of the game, and over the next few days people will be picking up Germany, French, and English copies at Essen.

Last week I was reading, watching, and listening to those early reviews simultaneously with you, but I’ve now had some time to compile my thoughts. Overall, as I would be when anyone enjoys one of my games, I was happy by the reviewers’ reactions, and they had some interesting constructive criticisms.

Today I thought I’d talk about the criticism shared by many of the reviewers. They said it in a few different ways (the weak story or the lack of huge changes), but I would sum up the prevailing thought as, “It’s not Pandemic Legacy.” I certainly don’t want to refute their opinions. But I would like to clarify a few things and set some expectations. Very minor spoilers regarding the mechanical structure of Pandemic Legacy are below.

I played Pandemic Legacy two years ago, and I really enjoyed it. It has a linear structure; that is, something that happens in the April episode in my game will happen in the April episode of your game. The story is interesting and compelling, and it includes a few big memorable moments. Every game of the campaign retains Pandemic as its core, with variations in goals or scenario-driven temporary mechanisms.

In almost all of the ways I describe Pandemic Legacy above, Charterstone is strikingly similar to it. I think that’s why I was a bit surprised to hear a few reviewers say that they expected big, sweeping changes throughout the Charterstone campaign, “just like Pandemic Legacy.”

Because the truth is, just like Pandemic Legacy, players frequently unlock new content in Charterstone, and the impact of that content ranges from tiny to huge. However, just like Pandemic Legacy remains a cooperative game about removing tokens from a board to save the world for every game of the campaign, Charterstone remains a worker-placement, village-building, optimization Euro game for every game of the campaign. Those core elements are featured in every game, even in the midst of scenario-specific goals and new objectives.

The main difference between the two (in terms of what the reviewers were talking about) is the following:

Pandemic Legacy’s story is cinematic while Charterstone’s story is player-driven. Pandemic Legacy uses a very well-written linear story to capture your imagination. Charterstone also has a narrative story arc, but it’s certainly not as strong as Pandemic Legacy’s story. That’s because the heart of Charterstone’s story isn’t the flavor text—it’s the story of your village’s growth. It’s about what you build, who you meet, and the strategies you employ. And the way you do those things will be wholly unique to your copy of Charterstone—the branching-path system and advancement deck ensure that your village’s story will be anything but linear (while being supported by the narrative arc and some big memorable moments).

I started off writing this post with the intention of saying that you might want to reset your expectations for Charterstone’s structure if you’ve played Pandemic Legacy. But honestly, I realized by writing this that the mechanical structure is remarkably similar. If you came away from Pandemic Legacy expecting Charterstone to unlock lots of stuff impacting the game in little and huge ways, surprise you with big memorable moments, enable your own story within the context of a narrative arc, and retain core gameplay while offering episodic variations…well, your expectations are correct!

I’d love to hear your thoughts and questions on this topic, given what you know about these two games.

***

October 18

The reviewer embargo for early copies of Charterstone is over! I will consolidate links to these reviews (all of which are clearly marked at their source as “spoiler” or “non-spoiler”) in this post throughout the day.

Rahdo (final thoughts): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJew1NY-Gv0

Rahdo (runthrough): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yH8Cf8OxyQU&t=0s

Rahdo (full game runthrough): https://youtu.be/aNtduKy6LL0

Geekdad: https://geekdad.com/…/charterstone-presents-a-unique-and-f…/

Dukes of Dice (first impressions no spoilers): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yK_GFEP0h_0

Dukes of Dice (spoilers review): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RLNUlvlaI80

Game Boy Geek review: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rcvmLL6pyo8

Board Game Quest review: https://www.boardgamequest.com/charterstone-review/

I have no idea what these reviewers will say about Charterstone. I’ll be reading/watching them in real time with you.

Some of you have asked if I’m nervous. I just want people to have fun playing my games, and reviewers are people too. Also, since there was no Kickstarter for Charterstone, there’s a some extra pressure.

In case you’re wondering why I had an embargo for early reviews, it’s so these reviewers have over a month to play the game without feeling like they need to race to be the first one to review it. I will send out a second wave of review copies in late November when the games arrive at the warehouse.

If you have any thoughts, reactions, or questions, feel free to post them in the comments below. And please make sure to mark them with (spoiler) if you want to talk about locked content.

***

October 11

October 11

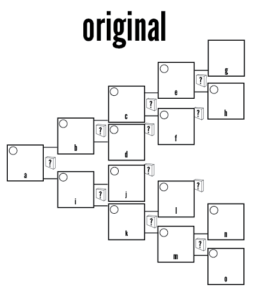

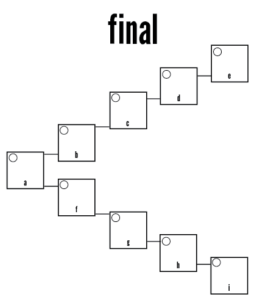

One of my favorite aspects to Charterstone is the “branching tree” unlock system.

Last week I talked about the “double helix” unlock system for the core story of the Charterstone campaign. It’s focused on the fate of the village and temporary rules.

But there’s a completely separate unlocking system in the game that each player has control over. This “branching tree” system is where each player will unlock most content in Charterstone (permanent rules, new components, new buildings, etc).

I won’t spoil what that content is, but I thought I’d give you a peek under the hood at the underlying structure of this system.

In this post you can see two diagrams. For a while I used the original system: Pretty much every time you unlock a new crate, you’re given content that allows you to follow 2 different branches. I liked that it never felt linear—you always had more than one path to choose from.

In this post you can see two diagrams. For a while I used the original system: Pretty much every time you unlock a new crate, you’re given content that allows you to follow 2 different branches. I liked that it never felt linear—you always had more than one path to choose from.

Unfortunately, playtesters weren’t fond of this system because of the level of uncertainty. Like, if they were faced with the choice of building C or D and then unlocking the corresponding crate, they didn’t know that D would lead to a dead end (more content, but no more buildings). Also, they had to spend so much time unlocking crates if they wanted to access all of the content in the game—it was too much.

I tried to fix this by giving each player a card that showed them the entire branching tree for their charter’s primary resource. It had tiny icons and names for each of the buildings. But it confused players more than it helped, because it made them think they could only construct those buildings, and the names of the buildings still didn’t really tell them what was in the crates.

So I made two important changes. First, I stopped trying to hint to players what was coming next. I found that when I removed those hints and cards, players stopped worrying so much about what they didn’t know and started having fun with the discovery of opening a new crate.

So I made two important changes. First, I stopped trying to hint to players what was coming next. I found that when I removed those hints and cards, players stopped worrying so much about what they didn’t know and started having fun with the discovery of opening a new crate.

Second, I restructured the tree so that there’s only one branch. I realized that even with one branch, you often still have several choices. For example, if I open crate B in Game 1, I have the choice to continue to proceed down that path or to unlock Crate F. I also consolidated the content inside of each crate so that players wouldn’t feel pressured to constantly unlock new content.

These changes helped significantly—it was one of those “ah ha!” moments of game design, and further testing showed that it worked exactly as intended. It’s particularly interesting when you start to gain building cards that originated in other charters, as it could set you down a completely different path and reshape your local economy.

I think the thing I’m most nervous about for Charterstone is how Euro gamers will respond to the uncertainty in the game. While you have full control over your decisions and you know that good things await when you open a new crate, you really don’t know what will be inside of it. I suspect that some people will love the feeling of discovery, while others will never quite be comfortable with it.

I think the thing I’m most nervous about for Charterstone is how Euro gamers will respond to the uncertainty in the game. While you have full control over your decisions and you know that good things await when you open a new crate, you really don’t know what will be inside of it. I suspect that some people will love the feeling of discovery, while others will never quite be comfortable with it.

How do you think you’ll respond to the uncertainty and discovery of the branching tree unlock system in Charterstone?

Brace yourself for next Wednesday, as that’s the end of the early reviewer embargo! I’ll post links to the reviews in my design diary post next week.

***

October 4

There’s a secret about Charterstone I’ve kept from you. It’s not a spoiler, just something that was difficult to describe without context.

When I revealed the rulebook (the “Chronicle”) several months ago, it was 5 pages. That’s an odd number of pages (literally) for a rulebook, isn’t it?

That’s because the Chronicle is actually 8 pages. Page 8 is an icon guide, and it has spoilers on it, so I definitely didn’t want to reveal that. But what are pages 6 and 7 for? Today you find out.

First, a little history. For a long time during Charterstone’s development, the Chronicle was a book of card sheets like those found in games like Mage Wars and Codex (see photo). I wanted the book to have a faux leather cover, something that felt precious and heavy in your hands as you filled it with rules and stories.

But there were insurmountable issues with this component. Originally I wanted the game to start with no rulebook at all, but as that changed, the book of card sheets no longer worked as well. The plastic sheets couldn’t be printed on or labeled, so it was frustrating for playtesters to have to count out X number of slots to insert rule 18, which may be unlocked out of order. Also, it was bulky in the game box, and the nice versions were very expensive.

So that’s how we ended up with the printed Chronicle, which I like much more. The game needed a starting rulebook—as slim as it is—and it plays better into the feeling of permanence than the book of card sheets did.

This brings us to the mysterious pages 6 and 7. What’s on them? You can see in the photo that there are 18 blank spots for story stickers.

I was hesitant to show this when I released the rulebook because Charterstone’s campaign is 12 games, not 18, and I thought it might be confusing or misleading to show 18 empty story slots in the Chronicle. The reason for this is that 6 sequential story cards are revealed right at the beginning of the campaign. They’re your introduction to the new village, and they walk you through the opening of components and the first few rule stickers.

It’s the other 12 story slots that correspond to each game. This is an element of the game that I’m REALLY excited for you to experience. At the end of each game, one player (someone who has accomplished a special goal) will get to scratch a concealing layer off of a specific guidepost card (see photo). That player will be presented with a choice, and that choice will impact the overall story (and the mechanisms). Like, it literally determines which story card is placed in the Chronicle.

That’s actually why it’s called a “Chronicle”—you’re chronicling the story of your village.

The reason this is special is that even though there is a cohesive plot to the story, the story itself isn’t linear—it’s more like a double helix. You have control over the history and fate of your village, not me. And one by one you’ll fill up those slots in the Chronicle with memorable moments until your story is complete.

You’ll be able to start your Charterstone story in a few weeks if you reserve a copy at Essen or in a few months if you get it from your preferred retailer.

In the meantime, what’s your most memorable moment in gaming over the last year?

***

September 27

In today’s Charterstone design diary, I’m going to talk about two elements that changed significantly during the development process.

The first is the advancement mat. As shown in the starting rulebook, there are a few different subtypes of advancement cards, and you’ll unlock more types over the course of the campaign. All advancement cards (except those that players have in their personal supplies) are kept in a big deck on the advancement mat, with 5 random cards always revealed face up. Whenever you gain an advancement card, you choose from those 5 face-up cards, then immediately refresh it.

The first is the advancement mat. As shown in the starting rulebook, there are a few different subtypes of advancement cards, and you’ll unlock more types over the course of the campaign. All advancement cards (except those that players have in their personal supplies) are kept in a big deck on the advancement mat, with 5 random cards always revealed face up. Whenever you gain an advancement card, you choose from those 5 face-up cards, then immediately refresh it.

However, this system changed quite a bit over time. One of the earliest iterations had no mat at all, just a big deck of cards requiring a blind draw. This jumped to the opposite end of the spectrum when I decided to have certain buildings draw specific card subtypes, resulting in a different mat for each subtype (and a LOT of shuffling).

Eventually those different mats merged into a single advancement mat, which wasn’t just more streamlined—it also offered a lot more variability from game to game, as the face-up cards at any given time are randomly revealed. This encourages players to try different strategies and tactics depending on what’s available.

The second is the progress track, which once operated in a very different way than the final version. In the final version, there’s a progress token that players advance on the track when they do something that progresses the village (construct a building, unlock a crate, or meet an objective). It scales based on player count, and when the token reaches the end of the track, the game ends (each player takes an equal number of turns).

For a significant part of the design, the progress track was actually a time track. I love the time track mechanism in Tokaido and tried to use in Charterstone, with different actions taking different amounts of time. Each player had their own token on the track, and the player whose token was furthest back in time was the current player.

I tried lots of different ways to get this to work, but it was a huge pain for players. Every turn they had to remember to not just place a worker or retrieve all workers but also move their time token. Time was valued so highly that players completely avoided actions with higher than 1 time cost. And if a player did jump ahead on the track, they could sit around for quite a while waiting for their next turn.

I finally realized it wasn’t working, and I scrapped it for a 3-row progress track (one for each of the progress categories). I quickly found it was more interesting and flexible to have a single track, and it flows really well.

***

September 20

I played my first 2 games of Charterstone on Sunday with my advance copy.

I was very, very nervous. Playtesting Charterstone with a rough prototype is very different than having the final version, particularly the sticker cards and rule-unlocking system. Legacy games are fragile systems—if one reference number is off or a single line instructing players what to do next is missing, it can lead to a lot of confusion.

So even though I had simulated the learning process with a fancy prototype and the pre-production copy, this was different. This was the real thing, and I was terrified of finding a mistake.

I was also nervous because, well, these are my friends, and I want them to have a good time. This is the case when we play any game, but especially when it’s one of my games.

Fortunately, so far, so good! We’re playing a 6-player game, and despite unlocking a lot of stuff in those first 2 games, we haven’t had any issues. The first game lasted about 90 minutes (you learn as you go), and the second game took 60 minutes. Everyone appears to be having a really good time.

I don’t have any photos from this game due to spoilers…however, I have something much better. Despite only receiving his advance copy last week, Rodney at Watch It Played already filmed and edited an excellent How to Play video. (The review embargo ends on October 18, but Rodney doesn’t do reviews–this view is informational, not opinionated.)

I highly recommend you watch this video. In fact, I recommend that you watch the video today and then use the video when you’re opening up your copy of Charterstone. You’ll still need to put stickers in the rulebook, but Rodney’s video will guide you through the rule-learning process for Game 1 perfectly, including cues to pause until certain things happen.

It’s so good that I wish I had watched it before teaching Charterstone on Sunday (or used it to teach the game to my friends instead of me!)

This is by far the biggest reveal about Charterstone yet. There are very minor Game 1 spoilers, but they’re on the level of seeing the game board or the most basic cards players will have access to at the beginning. Of course, if you want no spoilers at all, just save the video for the day you sit down to play Charterstone for the first time.

If you have any questions about the video, please let me know!

***

September 13

On Friday I received 11 advance copies of Charterstone.

Yes, 11. Kind of an odd number, right? (It’s literally an odd number.) The reason was that we were testing a 6-unit carton versus a 5-unit carton. The 6-unit carton is a little heavier, but it’s more space-efficient, so I opted for it.

These are final copies. No more tests or adjustments. I still had to inspect them, of course—this is the stage when everything has been printed and produced but not assembled. As soon as I approve the advance copies, assembly begins.

Fortunately, everything looked great. There was one component missing from the single copy of the recharge pack, but Panda had the component—they just forgot to put it in that box. The problem has already been solved.

Before I reveal the list, two things: One, your favorite reviewer may not be on this list, but do not fret. I will be sending out another dozen review copies when we receive the general supply of Charterstone in mid-November. Two, there’s a reviewer embargo set until October 18 at 8:00 am CST. That way these reviewers have over a month to play the game without feeling like they need to race to be the first one to review it. I’ll share links to the reviews on and after that date. Here’s whom you’ll hear from:

- Board Game Quest

- Dukes of Dice

- GeekDad

- Rahdo Runs Through

- Actualol

- Shut Up & Sit Down

- The Dice Tower

- GameBoyGeek

- The Secret Cabal

In the meantime, feel free to thumb the English version of Charterstone, which is newly added to the BBG Essen Spiel list: https://boardgamegeek.com/geekpreview/4/spiel-17-preview?q=charterstone

You can also check out growing number of interviews about Charterstone on this page, including a new video from Never Bored Gaming: https://stonemaiergames.com/games/charterstone/reviews-and-media/

***

September 6

I’ve found that inspiration comes from a variety of sources. I’ve written about how some of the roots for Charterstone were found in Lords of Waterdeep, Caylus, Ora et Labora, and village-building video games. But there are three other sources of inspiration, and they’re all over the place.

The first, and earliest, was Gloomhaven. Specifically, when I first saw the map drawn by Josh McDowell. This was years ago. It’s a lovely map, and one specific area caught my eye: the zoomed-in section depicting the town of Gloomhaven.

The first, and earliest, was Gloomhaven. Specifically, when I first saw the map drawn by Josh McDowell. This was years ago. It’s a lovely map, and one specific area caught my eye: the zoomed-in section depicting the town of Gloomhaven.

There was something about the way Josh depicted the town that really made me want to learn about each of the buildings in the town. I wanted to walk through Horn District, peddle some wares in the Coin District, and open shop in the square. I wanted to know the stories of those buildings.

Most of all, I wanted to see the town start from nothing and grow over time in its own unique, haphazard way. That’s when I first conceived the idea of Charterstone: Give players a blank slate and let them create their own, unique village. Let the players tell the story of that village, and give them ownership over certain buildings to create a unique and varied economy.

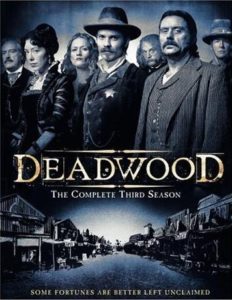

The second inspiration was the one that surprised me the most. Last summer I was already in the midst of designing Charterstone when I started to watch an old HBO show called Deadwood. I was not expecting it to have any impact on the design of Charterstone, as I thought it was a Western. Little did I know that it’s really a show about the rise of a town.

The second inspiration was the one that surprised me the most. Last summer I was already in the midst of designing Charterstone when I started to watch an old HBO show called Deadwood. I was not expecting it to have any impact on the design of Charterstone, as I thought it was a Western. Little did I know that it’s really a show about the rise of a town.

The biggest thing Deadwood taught me is a Charterstone spoiler, so I won’t go into that. However, I will mention an idea I considered before discarding it. As you can imagine, there are some adult themes in Deadwood, and many of those themes have specific buildings associated with them. These aren’t buildings that would be appropriate for the family audience of Charterstone, but I considered adding an optional “red-band” unlock pack for adult-only groups. In the end I decided not to do it—there are already plenty of buildings in Charterstone—but it was fun to brainstorm the possibility.

Last, one area that evolved quite a bit through Charterstone’s design process was the campaign story. There’s an ongoing mystery spread over 12 games, and at the heart of that mystery is the Forever King, the leader who sent you to create the village in the first place.

Last, one area that evolved quite a bit through Charterstone’s design process was the campaign story. There’s an ongoing mystery spread over 12 games, and at the heart of that mystery is the Forever King, the leader who sent you to create the village in the first place.

The inspiration for the Forever King came from none other than the works of Brandon Sanderson, one of my favorite authors. In several of his series, including Mistborn and Warbreaker, Sanderson uses the literary device of a mysterious but powerful leader to engage the reader’s curiosity. The nature of the Forever King is completely different than any of the leaders in Sanderson’s novels, but the core concept is similar.

When you create something, are you influenced by things like art, TV shows, and books? What gets your creative juices flowing?

Also, Feuerland currently has pre-orders open for Essen pickup of Charterstone (German version: https://www.feuerland-spiele.de/vorbestellung.php). When Matagot launches their pre-orders, I’ll let you know.

***

August 30

You may have noticed an odd note in the Charterstone rulebook: “Keep all cards face-up in your personal supply. Hiding cards isn’t allowed.” In Charterstone, players don’t have private hands of cards. Why is that?

A lot of the design decisions I made in Charterstone are crafted to create a specific experience. Usually that experience is one of discovery and permanence: You discover the board together, you unlock the secrets of the story, you construct buildings and use the remaining card to open a new crate.

But another key part of that experience is that it’s *shared.* Each player isn’t building their own village; rather, you have a charter within a shared village. You can place workers anywhere in the village. The length of the game is determined by what all players do, not just you. And so on.

So I decided early in the process that I wanted that shared experience to extend to the various types of cards players can acquire and collect. I don’t mean that the cards themselves are share—rather, it’s the information that’s shared. I want players to look around the table and see a variety of villagers populating the town, not other players huddled behind hands of cards.

If you want to experience what I’m talking about, the next time you play a game that doesn’t have super secret hidden information, instead of keeping your cards in hand, keep them face up on the table. Watch how it impacts your shared experience with the other players. I find myself doing this more and more in games, as it lets me focus more outwardly than inwardly.

Also, Charterstone is geared at least partially towards families, so having open hands makes it easy for parents to help kids understand their cards.

There is one important design challenge this presents: If all cards are face-up, they need to have information that can easily be seen from across the table. So, similar to Deus, most cards have both a big icon that depicts what they do and a textual explanation.

Do you play any games open-handed? How does it impact your experience?

***

August 23

What can I learn from village-building video games as the designer of Charterstone?

That’s a question I asked myself at several key points throughout the design process. While I very rarely play video games (nothing against them, but I’d rather be playing or designing tabletop games), I can learn a lot by watching YouTube videos about them. Below are a few common elements I discovered in village-building video games that I considered for Charterstone:

Lots of Buildings: Village-building video games have a huge focus on constructing and upgrading a LOT of buildings. That’s the whole point of the game, and it’s gratifying to see your village expand and improve. I found a few oddities in this mechanism, though. Even though there are a vast variety of buildings that look different, the differences between them are usually quite small. Most buildings slightly improve happiness, resource/money/food/worker production, or military. I tried to find a way for this to work, but in tabletop form it just didn’t end up being very interesting—with over 100 different buildings in Charterstone, I felt it was important for them to feel unique, not slight variations of each other. I did like the idea of upgrading buildings, though.

Villagers: A major focus of these games are the villagers themselves, whether it’s population as a scoring category or the acquisition of specific types of villagers to determine your path. For example, if you want to construct specific buildings or make them faster, you might hire more builders. I toyed around with various uses of people in Charterstone, and I eventually settled on two elements that are a bit of a spoiler, so I won’t go into them here.

Tech Trees: Pretty much every village-building video game I looked into had some kind of a tech tree, whether it was a branching path of technologies or of buildings. I ended up implementing this through the branching path of buildings you can construct, each one becoming more advanced than the last. There were a few months during the design process when you could see the full tech tree up front, but it seemed to confuse players into thinking that the only buildings available to them are those native to their specific charter.

Automation: Automation is a huge part of village-building video games. Most buildings you can construct end up producing something on a regular basis, whether it’s food, military, money, resources, etc. This type of thing works really well in a video game, but not so much on a tabletop game, particularly one that doesn’t feature rounds or phases. But I love engine building, so I eventually found a way to integrate automation (“income”) into some of the cards and buildings—it’s triggered by a symbol that appears several times on the Progress Track.

Feeding: Many village-building games (video games and tabletop games) feature feeding and farming as major elements. It’s often used as a rubber band for population. I decided not to include feeding in Charterstone. It’s not that your character doesn’t need food; rather, it’s just one of those things that happens naturally in the background, like sleeping or using the bathroom. I didn’t want to bog down players with the mundane.

Roads: I was surprised to find how many village-building games featured roads as core mechanisms, often to keep workers moving along specific routes or to speed up the transfer of goods from one part of the village to another. This didn’t seem to translate well into Charterstone, so I didn’t use it.

Forestry: Last, I notice that many village-building video games had players arriving at an uncharted patch of land, very similar to Charterstone. However, the land in video games often isn’t ready for you to build on, typically in the form of trees that need to be cleared. This just couldn’t work with stickers (i.e., remove a forest sticker from a board to clear the space and later construct a building there) due to production limitations.

Do you have a favorite village-building video game? What do you like about it?

***

August 15

I heard some good news from Meeplesource today! They expedited their custom character meeples for Charterstone, and they’ve been shipping them all over the world for the last few days. As a result, the meeples will be available at the booth we’re sharing with them at Gen Con (#2656). Charterstone itself won’t be at the booth, nor will I, but the folks at Meeplesource are very friendly, and they’re going to have a lot of different custom meeples and Stonemaier stuff there.

Because I’m heading to Gen Con tomorrow, I’m posting this week’s design diary entry today. As a thematic tie to the Meeplesource mention above, I thought I’d talk about a critical part of Charterstone’s design process: blind playtesting.

Prior to Charterstone, the last blind playtest I coordinated was for Invaders from Afar. Similar to core-game Scythe, we brute-force blind playtested it. That is, I reached out to our ambassadors, invited them all to blind playtest, and compiled as much data as possible to ensure that it was fun and well-balanced.

As a legacy campaign game, Charterstone is a completely different beast than Scythe. With discovery as a core feature of the game, I didn’t think it was the best idea to release a digital PnP, as the person building the prototype would inadvertently spoil quite a bit. Plus, I needed groups to commit to playing the game 13 times (12 campaign games plus 1 post-campaign game) over a short time period—having data and feedback for just 1 or 2 games wasn’t helpful, nor was it useful if it took a group 2 months to complete the playtest.

So I implemented a completely different blind playtest process: 4 waves over 6 months, a total of about 20 different groups, over 250 games played. Cynthia Landon, the co-owner of Meeplesource, was the lead playtester for one of those groups, hence why I’m talking about this today.

For each group, I asked our prototype helper, Josh Ward, to create a prototype from scratch (fortunately, we were eventually able to reuse some of the contents of each game). I had him send those prototypes to 5 different groups for each wave of playtesting, each at a different player count (solo playtesting would happen later).

Each lead playtester was expected to film the first game, something I learned from the Pandemic Legacy process shared by Rob Daviau and Matt Leacock. It was painful to watch those videos, because it’s quickly apparent when rules are poorly written or a mechanism doesn’t work as well as it should, but I found it incredibly helpful to watch people stumble through that first game on film.

Over a 2-week period, groups would play through the 13 games, entering data and feedback on a detailed Google Form and taking photos of the game state. I tracked the game length, certain legacy decisions, and player ratings, in addition to questions like the following:

–Was there an overpowered strategy? Or was there a boring/repetitive (yet successful) strategy?

–What was the most frustrating thing that happened during the game? Why was it frustrating?

–Which rules did you play incorrectly? Were there any rules confusions?

–If the game lasted longer or shorter than you feel it should have, why did you feel that way and what was it about the game that made it too long/short?

At the end of each wave of blind playtesting, I paid the lead playtester for their time (I typically don’t do that for blind playtests, but for Charterstone, they were doing a job with very specific expectations—they weren’t volunteering at their leisure), and sat down with a huge amount of quantitative and anecdotal data to sort through.

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to these blind playtesters. It’s a sacrifice for them to spoil many aspects of the game and stumble through the campaign using a prototype instead of the final version, but the game is so, so much better for it. Charterstone wouldn’t even exist without these blind playtesters.

***

August 9

I need to start this week’s Charterstone post with some bad news.

I need to start this week’s Charterstone post with some bad news.

Our manufacturer, Panda, has actively been actively printing Charterstone for a while now. It’s going well…with one exception: the sticker cards.

As you can see in the image below, each sticker card is comprised of multiple layers. There’s the sticker material itself (the top layer), then the waxy paper the sticker is peeled from (middle layer), which is glued to the regular cardstock (bottom layer).

These cards are printed on giant sheets and then diecut by a giant, very sharp machine.

Normally this machine is very fast. With Charterstone, every time it cuts a card sheet, the blades get a little bit of glue on them. This glue accumulates to the point each day that the machine must be stopped and the blades must be cleaned.

Compounded with a few other lesser factors, this has resulted in Charterstone’s estimated completion date (at the factory) changing from September 15 to as late as October 8. Because of the way Thanksgiving week impacts freight shipping in the US, I had to adjust the retail release date from late October/early November to December 12.

So, that’s the bad news. It’s far from ideal, but I’d rather let you know now than the last week of October.

So, that’s the bad news. It’s far from ideal, but I’d rather let you know now than the last week of October.

The bright side is that some of our international partners will likely air freight some copies in for Essen Spiel. I think you’ll see French and German copies there, and I may sell some English copies to those partners for Essen too.

The other good news is that all of the non-printed components—those that are usually more likely to slow down production of a game—are going great. These photos are of most the non-printed components you’ll see when you first open the box: They’re the standard player pieces, coins, and resources.

Thanks for your patience, and I look forward to hearing what you think when you play Charterstone in December.

***

August 2

Yesterday we released the Charterstone teaser trailer, which we’ve been working on for a while. I wanted to share it with this group today and talk about some of the people and decisions that went into it.

Step 1: SCRIPT. I created a PowerPoint slideshow to storyboard the video, with each “scene” containing 1 line of text and some images. I typically aim for 10-12 slides so the video won’t be too long. My main goal with the script is to pair it with visuals—some of them animated—to convey concepts that I can’t express as well through text or static images. That’s particularly the case about halfway through the video where a building sticker is removed from a card and placed in a charter.

Step 2: VOICEOVER. I sent the slideshow to voiceover artist Alex Hall. I had met her recently during the filming of a web series about game design, and I thought her clear and friendly voice fit the tone of Charterstone. She sent me a few different audio files and I picked my favorite. It’s important that this step came before Step 3, which requires me to know the exact length of the video.

Step 3: MUSIC. Now that I knew the length of the video, I could buy some music for it. I chose premiumbeat.com’s “Production/Film Scores” genre and found a great variety of music there. Again, I went for something light and cheery for Charterstone’s video.

Step 4. INTRODUCTION. This wasn’t in my original plan, but I decided to put about 10 seconds of me talking to the camera at the beginning of the video for a few reasons. Primarily, because we’re not using Kickstarter for Charterstone, I wanted to show people that Stonemaier hasn’t gone corporate—I want to connect with you on a face-to-face just like before. Secondarily, I wanted to assure people that the video would be spoiler-free.

Step 5: EDITING/ANIMATION. When all of the content for the video and the game itself was ready, I sent it off to the maestro that is Josh McDowell. He’s the one who makes the video look so polished through editing, animation, and probably a lot of other stuff I don’t even know about.

You can watch the final result here.

***

July 26

Let’s talk about the recharge pack.

When people started engaging in the Charterstone Facebook group in January, someone mentioned the idea of a recharge pack. It gained enough traction that I added it to our Future Printing Request Form to gather some hard data. (https://stonemaiergames.com/future-printing-request-form/)

The idea was that after you play a 12-game legacy campaign of Charterstone, you will have permanently altered a number of components. The game is designed so you can continue to play your copy post-campaign, but you no longer have that feeling of starting from scratch and building a village with your friends. The recharge pack would refresh all components that were permanently changed during the original campaign while allowing the wooden tokens and metal coins to be reused. And the game board is double-sided, so you’ll just flip your board over and play on the back side.

The idea was that after you play a 12-game legacy campaign of Charterstone, you will have permanently altered a number of components. The game is designed so you can continue to play your copy post-campaign, but you no longer have that feeling of starting from scratch and building a village with your friends. The recharge pack would refresh all components that were permanently changed during the original campaign while allowing the wooden tokens and metal coins to be reused. And the game board is double-sided, so you’ll just flip your board over and play on the back side.

My original plan was to poll people after they finished the first campaign to see if they wanted us to produce the recharge pack. That way you could make an informed decision as to whether or not you wanted to play again, and Stonemaier wouldn’t need to invest heavily in something if only few people were interested.

However, the request survey indicated that my concerns were unfounded. To date, 2300+ people have indicated that they want the recharge pack. That’s 30% of the people who have indicated on the same form that they want Charterstone. So I recently decided to move ahead with the recharge pack as part of the first print run of Charterstone.

This led to some creative problem solving largely inspired by our German partner, Feuerland. I wanted to offer the recharge to our international partners, but I knew that many of them would want fewer than the 1000-unit minimum for any printed component. Also, despite not having wooden tokens or metal coins, the recharge pack is quite expensive to make.

This led to some creative problem solving largely inspired by our German partner, Feuerland. I wanted to offer the recharge to our international partners, but I knew that many of them would want fewer than the 1000-unit minimum for any printed component. Also, despite not having wooden tokens or metal coins, the recharge pack is quite expensive to make.

The solution was to create a universal box for the recharge pack. You can see the image here—the bottom of the box features all 8 languages even though the contents of each box will be for a specific language. When Panda packs the box, they’ll check the box next to the language and send it to the corresponding partner.

The end result is that you can double the campaign/legacy value of Charterstone for less than half of the price of the original game. Charterstone is $70; the recharge pack is $30. If you want to add a copy to your pre-order with a retailer, just tell them you want STM701.

This is another great example of the positive and creative power of the Charterstone community. Thank you!

***

July 19

A fun but nerve-racking step of the game-manufacturing process is the pre-production copy (PPC). This is a copy of the game that looks and feels like the final product, but it’s really just a close approximation.

The purpose of the PPC is to ensure that all of the printed components look and feel exactly as they are supposed to. We check for the type of paper and cardboard, that the card backs match the fronts, and that all of the diecut materials are aligned properly. With the approval of a PPC, a manufacturer can finalize the various steps of the printing/cutting process, and production can begin.

I received the Charterstone PPC this morning, and the good news is that 99% of it looks fantastic. There are a few tuckboxes that need minor adjustments, and the “insert” (which, given the amount of stuff in the Charterstone box, is a pretty small piece of cardboard with the function of preventing stuff from sliding around) could use a few tweaks, but overall it’s great. These are things Panda can fix by the end of this week, which keeps us perfectly on schedule.

So today I’m going to show you a top-down view of unboxing the Charterstone PPC, layer by layer. No spoilers here, and I’m not going to open any of the tuckboxes (even though you could open most of them without spoiling anything).

Will the Index hold sleeved cards? When the cards are in use, they’re kept in the Scriptorium and the charter chests, not the Index. Those boxes do fit sleeved cards, but we highly recommend not sleeving cards during the campaign, as there are lots of cards you need to interact with (remove stickers from, write on, scratch off, etc). If you had to pause the game to sleeve new cards every time they’re added to the game during the campaign, it would be pretty annoying.

***

July 12

(this 3-part post was written by Morten Monrad Pedersen)

A long time ago, I concluded that Jamey, enjoys throwing curveballs at us in “Team Automa” (we make solo modes for the games he publishes), so that we don’t grow complacent, but get new tough challenges each and every time.

Because of its legacy aspect, Charterstone is a new breed of curveball: Getting humans to adapt to a game where major rule changes are implemented between plays and the game board itself frequently change is challenging, but you try to make a stack of cardboard with the intelligence of, well, cardboard, handle that same challenge and you’ll feel our pain and agree that Jamey is a sadist.

Not only did he do that to us, he also added, “by the way, the Automa rules for handling all those changes should only take up a few cards.”

Since we didn’t want to make Jamey think that he had beaten us, we one-upped him by challenging ourselves not only to make a good solo game, but also to make the game work with any number of humans and Automas, and to enable Automas to stand in for players who can’t make it to a game night.

So, we locked ourselves in our virtual office together with a crack team of elite playtesters and banged away on the Automa system until we got all the challenges beaten into submission. We hope you’ll find that we succeeded in doing so, once the game gets released.

As an aside, I can tell you all that we in Team Automa are firmly convinced that very soon Jamey will announce that the has acquired the rights to 504 and want an Automa that can play all the 504 games included in the box while having a rulebook the size of a stamp.

********************

Since the release of the Tuscany expansion, my team and I have been doing bots (we call them “Automas”) for all Stonemaier releases. They’ve been aimed at making the games playable solitaire.

Over time, though, we’ve gotten an increasing number of requests for adapting our Automas for multiplayer games, so that 2 players might play a 3- or 4-player game, if they like the game better at a higher player count. For Scythe, we also got a ton of requests for making games playable solo with multiple Automas.

We’ve accommodated these requests by making variant rules available for free on Board Game Geek. For Charterstone, though, we decided that you should be able to play the game with any combination of humans and Automas out of the box.

So, if at the start of your campaign, you think that more players might join the campaign later on, you can let Automas keep their charters warm until then, so that they have something more interesting and competitive to take over.

You can also start out with an Automa or two in the game, if you’ll have a low player count campaign and want a busier village. Alternately, you can also play your first game without them and then add them in for the second game, where you should be comfortable with the core rules.

If you find out that you don’t like the Automas? Well, then you can simply ban them from future game nights and let their charters become inactive or you can replace them by human players. I’m standing here ready with buckets of comfort ice cream and piles of Kleenex in case you ban them and they come crying home to daddy.

*****************

Charterstone is intended to be played with the same group of players throughout the campaign. Getting the exact same group together for 12 plays can be, well, let’s say challenging. Therefore, the rules support players leaving or entering the campaign (temporarily or permanently), but it’s not ideal.

Since we created bots (called Automas) to make Charterstone playable solitaire, it seemed natural to allow a bot to stand in for a human player who’s not there. Instead of that player’s charter being inactive. This not only scores the various kinds of points for the charter, it also gives the other players a play‑experience that’s closer to what they’re used to.

This presented an interesting extra challenge to us in “Team Automa”. Normally we can design our Automas with solo players in mind. This matters because solo players are used to running bots. They’re OK with putting in some effort to learn the bot rules, and spending time each turn to carry out the bot’s actions.

Multiplayer gamers, on the other hand, are not used to doing this and are often less inclined to spend the time and effort required. I’m not saying that multiplayer gamers are less intelligent or less patient than solo gamers, I’m simply talking about a difference in preferences and experience levels regarding bots in board games.

So, we needed to make the Automa system as simple as possible without compromising the solo experience and we put in a lot of effort to achieve this.

- We boiled the system down to a few streamlined actions, that still mimic the core interactions you have with a human player.

- We limited ourselves to using the icons of the base game.

- We made the cards that implements the Automas simpler and easier to read, than we did in our Automa for Scythe.

In most cases, players are able to tell a fellow gamer apart from a stack of cardboard and the Automa is not a perfect replacement for human player. We hope, though, that our work will improve your game experience, when a player can’t make it to game night.

If you’re interested in learning the approach we use for making Automas and perhaps use it yourself, you can read an introduction here.

***

July 5

We’re doing something with Charterstone that we rarely do: The first print run will be in 8 different languages.

Our typical method is to make the first print only in English, and while it’s being manufactured, international partners have ample time to work on their translations. That way the English version isn’t delayed by international versions, and international versions aren’t rushed along. My detailed thoughts on this are here: https://stonemaiergames.com/kickstarter-lesson-198-translation-localization-and-language-independence

So why take a different approach with Charterstone? Two main reasons: One, the game isn’t language independent, and the rulebook evolves over time—it’s not like other games where we can simply offer digital translations of the rules. Two, we didn’t want to make non-English speakers wait 4 extra months to unravel Charterstone’s secrets. That didn’t seem fair.

Also, this is what many of our international partners requested. They could have waited until the second print run, but they chose not to. And I’m grateful they didn’t—I’ll explain why in a moment.

First I want to mention how this process works, because it wasn’t easy, and I really appreciate 7 of the original partners (out of 9) sticking with us. On the Stonemaier side of things, we started having final versions of the Charterstone files ready in May. These were fully tested, proofread files. When they were ready, we uploaded the source files to international partners for translation. Their job was to translate the files, export them to printer-ready PDFs, and upload them to Panda.

At the point when the partners started to receive the digital files, they had not yet actually played Charterstone. This is because the version of the game I wanted them to play isn’t something that my prototype maker—as good as he is—could create, especially the sticker cards and numerous custom components. So it really wasn’t until the partners got the fancy prototype from Panda that they truly knew what the game was. Several of them proceeded to play marathon sessions of it.

This was in late May, the timing of which was crucial, because we started making the non-printed components for Charterstone in early June. Partners were required to provided their quantities before the non-printed production began (though they could decrease that number during June if necessary).

June was a really intense month for these partners, as the hard deadline for the final files was June 30. It was a really tight timeframe for the amount of content that needed translation. The June 30 date was so important because we wanted to release Charterstone in time for winter holidays (late October/early November).

But, amazingly and miraculously, these partners pulled it off: Feuerland (German), Matagot (French), Maldito (Spanish), Lavka Games (Russian), Ghenos (Italian), Surfin Meeple (Chinese), and Ludofy (Brazilian-Portuguese).

Not only that, but they all helped to make the product better. Our proofreaders are great, but when you have translators who are invested in getting every word, icon, and number right, they catch stuff that proofreaders miss. Every one of those partners contributed to making Charterstone a better game in every language.

Also, having these partners involved in the first print run helped to increase the total quantity to 56,500 games. That has a big impact on the per-unit cost of the non-printed components.

If I had to change one thing about this process (other than not having such a tight deadline) would be that we should have sent the final English files to Panda for digital proof review before we sent those files to the various partners. There were a few things that were out of alignment or were low res, and instead of making such changes before the partners got them, we’re now in a situation where each individual partner has to make those changes this week. But they weren’t too bad.

Thanks to all of our international partners and their fans for supporting Charterstone’s first print run! I’m so happy that thousands of people around the world will be playing Charterstone at the same time in November.

***

June 28

You’ve now seen the starting rulebook for Charterstone, so you know the core mechanisms. Over time I’m going to discuss the evolution of how certain elements changed during the design process. Today I’m going to jump to the juicy bit: unlocking crates.

You’ve now seen the starting rulebook for Charterstone, so you know the core mechanisms. Over time I’m going to discuss the evolution of how certain elements changed during the design process. Today I’m going to jump to the juicy bit: unlocking crates. This problem was compounded by the fact that there are 3 different card types in Charterstone. That is, 3 completely different card compositions: regular cards, sticker cards, and scratch-off cards. Each of those card types needs its own card sheet (or multiple sheets). So if a crate contains 2 regular cards and 1 sticker card, it’s not like those cards can be printed sequentially. They would have to be pulled from separate decks and placed inside the envelope.

This problem was compounded by the fact that there are 3 different card types in Charterstone. That is, 3 completely different card compositions: regular cards, sticker cards, and scratch-off cards. Each of those card types needs its own card sheet (or multiple sheets). So if a crate contains 2 regular cards and 1 sticker card, it’s not like those cards can be printed sequentially. They would have to be pulled from separate decks and placed inside the envelope.  I didn’t want to let go of the envelopes, but I knew the risk of mispacked envelopes was too high. So after much teeth grinding, I thought of a solution: We would number the cards sequentially, with breaks between each of the 3 card types. Panda would print the cards, sort them sequentially (an automated process), shrinkwrap them into decks, and place them inside the Index tuckbox (see photos). Whenever a player opens a crate, they’ll refer to the Index Guide, which will tell them exactly which cards to extract from the Index.

I didn’t want to let go of the envelopes, but I knew the risk of mispacked envelopes was too high. So after much teeth grinding, I thought of a solution: We would number the cards sequentially, with breaks between each of the 3 card types. Panda would print the cards, sort them sequentially (an automated process), shrinkwrap them into decks, and place them inside the Index tuckbox (see photos). Whenever a player opens a crate, they’ll refer to the Index Guide, which will tell them exactly which cards to extract from the Index. Of course, there are a few things to be unlocked that aren’t cards. They’re referenced on the Index Guide, and they’re stored in labeled tuckboxes.

Of course, there are a few things to be unlocked that aren’t cards. They’re referenced on the Index Guide, and they’re stored in labeled tuckboxes.***

June 21

Charterstone has somewhere around 300 unique illustrations, yet I’ve never formally introduced the artists. That changes today.

The first step, dating back to December 2015, was to select an artist for the buildings. After discussions with Stonemaier insiders (Alan, Morten, and Christine) and one of the best art directors in the business, Ed Baraf of Pencil First Games, we decided to work with Angga Satriohadi of Gong Studios. Angga created the announcement image, and it was a pleasure to work with him and his team on the 100+ building illustrations they created and revised. Angga also illustrated some of the people who will populate your village. I think Gong Studios may have also worked on the game Dice City for AEG.

You’ll note that most of the buildings in Charterstone have an exaggerated style to them. The reason for this is to help players identify (mostly for thematic reasons) what they do from across the table. You’d have to get really close to see a beer mug on a tiny sign hanging from a tavern, but if the tavern itself is shaped like a giant keg, you can understand what it is with a quick glance.

While working with Gong Studios, I found myself admiring the work of Mr. Cuddington more and more. “Mr. Cuddington” is the studio name of a husband-wife team of illustrators (David and Lina). They’ve worked on a number of games for Roxley Game Laboratory, as well as the recent Druid City game, The Grimm Forest.

I thought Mr. Cuddington would be perfect for the characters and box for Charterstone, and I was very fortunate that they had some availability. At the time, neither of us knew the full scope of what they would create for us. I can’t say more without spoiling anything, but David and Lina created a ton of illustrations for Charterstone. I also discovered that they are incredibly adept at card layout, board design, and icon creation. They are the perfect creative partners.

I’m incredibly grateful for the time, effort, and creativity that both Gong Studios and Mr. Cuddington put into Charterstone.

***

June 16

The day has come for the Charterstone rulebook to be revealed. First, some context.

One of my favorite features of Risk Legacy (and, later, Pandemic Legacy) was that it was really easy to play the first game. It helped that I had played Risk a lot as a kid, but there were also these big gaps in the rules where stickers would later be placed. Rob Daviau could have introduced a dozen new rules from game 1, but instead he slowly unraveled them, easing players into new systems through the joy of discovery. It was brilliant.

Risk and Pandemic have the benefit of a lot of people understanding the core rules. Charterstone does not have that benefit. There is no existing foundation. So I decided it was incredibly important to ease players into the rules organically over time, even giving players control over when new content is unlocked so you won’t be overwhelmed.

There was a certain point in Charterstone’s design when the rulebook started off completely blank. When you opened the box, there was just a little note saying, “read card #1.” Card #1 had some rules on it for you to learn, and after you understood them, you’d peel a sticker off the card, affix it to the rulebook, and continue to card #2.

We tested this for a while, but I realized that when rules are introduced that way, there’s a much higher chance of players missing something important than when there’s some foundation for them to start with. So I moved certain rules to the rulebook—now called the Chronicle—while certain other cards are unlocked via the system I described above. As indicated on page 1 (which I revealed in this group last week), the game encourages at least one player to read through the Chronicle before Game 1.

So that’s what you’re going to see today, the foundational rules of the game. There are holes in these rules that are filled at various times throughout the campaign, and sometimes you’ll even have new rules replace older ones, all through the system of peeling a rule sticker off a card and placing it in its assigned spot in the Chronicle. That’s why the rulebook looks like an assortment of cards.

I applaud you if you read all this before looking at these pages! Without further ado, here is the Charterstone rulebook, which is perfectly fine to read in advance of Game 1.

Oh, and the Chronicle will be available in all 10 languages of the first printing in a few weeks. The translators are currently working on it.

***

June 7

A long time ago, when I knew that Charterstone would not be on Kickstarter, I decided to put metal coins in every copy of the game.

A long time ago, when I knew that Charterstone would not be on Kickstarter, I decided to put metal coins in every copy of the game.

Sure, I could have sold them separately as we do with the Viticulture and Scythe coins, but I really liked the idea of including something that felt like a treasure inside a legacy game. Also, even though you can play Charterstone after the 12-game campaign, if you decide not to, at least you have 36 metal coins to use in other games.

Also, I wanted Charterstone to be a game where you can open the box and proceed to play it—no need to punch out a bunch of tokens.

Originally I wasn’t even going to tell people that metal coins are included in Charterstone—it was going to be a surprise when you opened the box. But given the expense of adding them to the game, I figured it was best not to keep them a secret.

You’ll notice that the coins are all $1 denominations. Early in the Charterstone design, players had storage limits that applied during each game. You could only hold a certain number of resources, coins, etc unless you expanded your storage capacity. There were slots in your tableau that could hold 1 coin each, and I wanted to avoid the confusion caused by different denominations (i.e., can each slot hold $1 or 1 coin of any denomination?).

You’ll notice that the coins are all $1 denominations. Early in the Charterstone design, players had storage limits that applied during each game. You could only hold a certain number of resources, coins, etc unless you expanded your storage capacity. There were slots in your tableau that could hold 1 coin each, and I wanted to avoid the confusion caused by different denominations (i.e., can each slot hold $1 or 1 coin of any denomination?).

However, I quickly realized that I don’t particularly enjoy storage mechanisms. While they can be a useful construct, I’ve never met a storage mechanism that increased the fun factor. However, in a campaign game, it is fun to be able to carry over some components from one game to the next. So I shifted the storage mechanism to something called “capacity,” which you’ll learn more about after you complete Game 1.

Once I knew there would be only $1 coins, the challenge was deciding the quantity and quality of them. I eventually selected 36 as the quantity—you need exactly 36 coins in Charterstone, no more, no less. As for the quality, I wanted each coin to feel substantial heavy. So I made them 3mm thick (compared to the 2mm Scythe coins—see photo).

Some people have asked if we’ll be selling these coins separately, and I’m 99% sure the answer is no. If a significant number of people love the coins and want to buy more for their other games (remember, Charterstone has a hard limit of 36 coins—you’re not allowed to use more), I’m open to the possibility, but I’ll wait until people actually play the game before I add them to our future printing request form.

***

June 2

A month or so ago, I sent the final prototype files for Charterstone to both my graphic designer and my manufacturer, Panda. The latter was a bit unusual–typically we only send Panda the final, printer-ready files, not the prototype files.

But Charterstone is an unusual game. I felt it was important for me to have a copy that functioned like the final version. For example, up until this point the playtesters and I have been cutting the building hexes off of cards, as there wasn’t a way to create card prototypes with hex stickers. I wanted to see how the unpeeling experience felt and functioned, among other things.

The other reason I asked Panda to create these special prototypes is so we could have something to send to our international localization partners. They’ve been taking it on blind faith that Charterstone is a game they want. Each of them got 1 copy of the nice prototype.

Alan and I sat down with the prototype at our weekly meeting on Wednesday to simulate the process of opening the game (when you sit down for your first play of Charterstone, there are instructions and story elements on a series of cards). Even though we’ve done this before with rough prototypes, it was incredibly enlightening to use a version that felt “real,” and I tweaked some of the instructions as a result to foolproof it (Alan does a good job of playing the fool when necessary).

I also realized that a few of the tuckboxes (one that holds global components from game to game, one that holds components you no longer need, and one other box with secret stuff) are too small. Fortunately, there’s horizontal space in the box available for adjustments.

I’m really grateful that Panda put forth the effort and resources to make these nice prototypes for us and our international partners. Overall, I’m really happy with the functional results, and I look forward to testing out the pre-production copy in 1-2 months.

For now, here’s a quick unboxing video of the nice prototype!

(After watching it, make sure to click on the link in the description for the real video, which shows Charterstone’s box size.)

***

May 24

Today let’s talk about Charterstone’s resources.

Today let’s talk about Charterstone’s resources.

From the earliest stages of the design process, resources were part of Charterstone. I wanted each charter to have a specific role to play in the village, and the resources would be the building blocks of those roles.

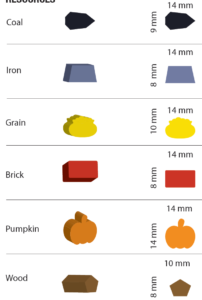

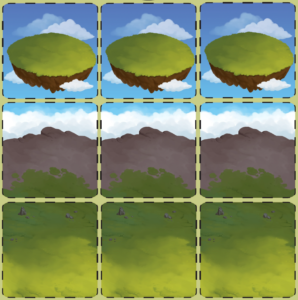

I knew it would be a 6-player game and that players would both be constructing buildings with the resources AND spending those resources at buildings, so I selected 6 resources that would meet those requirements: coal, iron, grain (for thatched huts; this was originally reed), brick, pumpkin (giant pumpkins), and wood. You can see in the charter image here that each area is primed for a specific resource—wood for the green charter (top) and grain for the yellow charter (bottom).