I feel like generative AI is everywhere these days. When I create a video on StreamYard, it asks me if I want its AI to create a thumbnail image. When I compose a newsletter on Mailchimp, it prompts me with an option to write the message with AI. And so on.

Frankly, I’m not interested.

Stonemaier Games does not, has not, and will not use any form of AI to replace or augment* creative work. If we’re creating something, we want it built from the ground up by talented people from different backgrounds, perspectives, and cultures, not an algorithm (especially not an algorithm that borrows without permission or at least proper credit from the original artists).

*Part of the conversation resulting from this article is about how there are commonly used tools (like in Adobe Photoshop) that artists use to touch up illustrations, which I support. Are they AI? Not necessarily. But they are augmentations. Much of this article is about these gray areas.

Despite this commitment, I also admit that AI has impacted Stonemaier Games for years, as our digital games feature AI opponents. Have you played Scythe Digital, Wingspan Digital, Charterstone Digital, or others? Odds are that you’ve played against the AI. Not really generative AI, but certainly in the same realm.

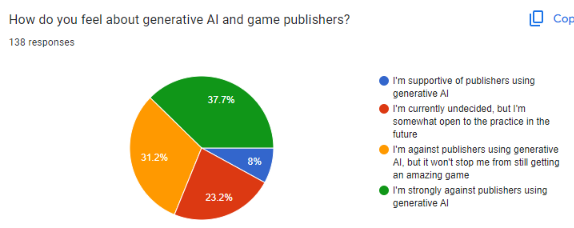

With this in mind, I recently polled Stonemaier Ambassadors to see how they’re feeling about generative AI. I first asked about their general response to generative AI in tabletop games:

These results surprised me a bit–I expected more people to strongly oppose the use of generative AI, especially with the recent uproar about Terraforming Mars and the new version of Puerto Rico. Yet this is somewhat in line with what I’ve seen about eco-friendliness: about a third of people like the idea of it, but the quality of the game comes first.

It’s also notable, however, that only 8% of respondents said with no disclaimers that they support the use of generative AI.

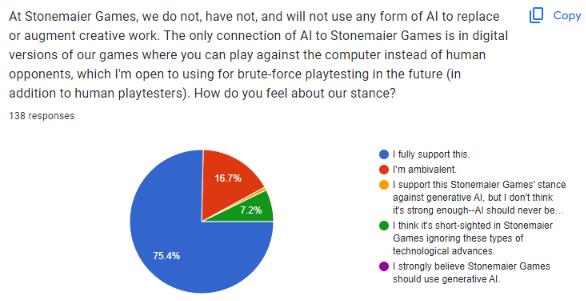

I asked about this before making our stance clear in the question that followed:

I don’t think a single person said that they strongly believe we should use generative AI (though around 7% of people said that our approach might be short-sighted). The answer I was most curious about was to see if some ambassadors thought our stance wasn’t firm enough, and a few people fall into that camp.

Specifically, I was talking about a future where you can feed a near-final prototype into an AI playtest bot and have it spit out 10,000 games’ worth of data in a few minutes. I don’t see this as replacing human playtesters at all (the amount of playtesting our paid lead playtesters perform and coordinate will continue to be just as robust as ever, if not even more so), but it could be helpful for identifying the types of circumstantial, niche, and asymmetric imbalances that publishers can only discover after has been played thousands of times.

None of this changes my overall stance on generative AI, but it’s good food for thought, as is the following:

- Privilege: We can proudly say that we pay artists for the creation of hundreds of illustrations in a single game (Wyrmspan, for example, has over 230 unique illustrations by Clementine Campardou), but what about a first-time designer looking to self publish their game on a shoestring budget? Generative AI is far from the only option, but I can understand why it might offer a different value proposition to that creator than to Stonemaier Games.

- Prototype Art: When I was designing Viticulture in 2011 and 2012, I added some temporary placeholder photos from Google Image searches to the playtest prototypes so they wouldn’t look so plain. Is it any different for a designer to use generative AI to add a little flavor to their prototype? While it isn’t “art” that we would ever use, I don’t mind if someone submits a prototype like this.

- Search Engines: A few months ago we experimented with the addition of a site-specific search engine with an AI foundation. I found it more helpful than a Google search to unearth and summarize older articles on various topics–I’ve written these twice-weekly articles since late 2012, so there’s a lot of text to dig through. Ultimately the search engine’s plugin messed too much with the coding of our website, so we removed it.

While I’m truly not interested in having AI generate art or text for anything we make at Stonemaier Games, I’m curious to hear your thoughts about the gray areas like those I mention above: AI opponents in digital games, brute-force playtesting, privilege, prototypes, search engines, and beyond. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

UPDATE (April 24, 2024): Board Game Wire has an article on this topic in which I answered some questions.

***

If you gain value from the 100 articles Jamey publishes on this blog each year, please consider championing this content! You can also listen to posts like this in the audio version of the blog.

56 Comments on “Generative AI? Not for Us!”

Leave a Comment

If you ask a question about a specific card or ability, please type the exact text in your comment to help facilitate a speedy and precise answer.

Your comment may take a few minutes to publish. Antagonistic, rude, or degrading comments will be removed. Thank you.

AI opponents in digital games, brute-force playtesting, prototypes, search engines, etc. all seem reasonable to me. I’m even mildly open to it in some meager marketing endeavors, especially for indy creators but never to take away from the need for human artists. I believe AI is a tool and nothing more.

I really don’t mind new creators using AI art in their final product, so long as they are blatantly up front about it. I’m not cool with people lying about this or intentionally leaving out info on this matter. Would I buy a big budget item made with AI art by a bigger publisher. I want to say probably not, but if the product was right? I honestly can’t say. I don’t always pay detailed attention to who the artist(s) is when I buy a game.

However, I never want to take away from the very human element in my own personal endeavors either.

I have not used AI art in the final product of any of my games (or even in the prototyping for that matter), but I do use stock images on occasion in my prototyping and lower cost artwork for my final products (granted, I’m a super indy publisher and can only afford so much). I treasure the art that has been created for my games, more than some reviewers do. And, I intend for all my art, to the best of my knowledge, to be created by artists who have a history of art that maintains their stylistic thumbprint in its work. Artists can often be recognized for the similarity in their art style, and this helps determine credibility.

I also personally involve my own Art Direction, Editing, and Graphic Design as well in making the artwork fit the project every step of the way.

I deeply value drawing from a number of artistic styles as I approach my world-building from different perspectives and have utilized 5-10 different artists to date, only 3 whose work has shown up in released products at this point (but hopefully more to come).

I only say all this to point to the fact that you’re not alone in this, but I believe your data tells you that.

Jamey,

It seems as though you place a high value on creative work, would that be fair to say? I agree with this wholeheartedly. I think the value of jobs is highly important. Even if it means investing a few extra dollars into the creative work.

Can you tell us more about how this stance is different than the stance to manufacture your games in other countries where labor costs are cheaper than they would be if you manufactured your games domestically?

Thanks in advance,

Frank

Frank: I think it’s absolutely fair to say that I place a high value on creative work, no matter the location or nationality of the people doing the work as long as they are treated fairly and paid a fair wage (as is the staff at Panda, a Canadian company with their main factory in Shenzhen).

Jamey: thanks for your response!

Can you tell us about your choice to manufacture games in China rather than domestically?

I seem to remember from one of your livecasts years ago that the major driving factor was cost, do I have that right?

I see a conflict with your point of view of being willing to pay more for artists than use generative AI and the choice to manufacture games in another country because of cost.

I think my responses here are largely because I view my work in manufacturing as an art. We invest time and creativity in optimizing and engineering manufacturing solutions. It may not be the “traditional” art that people think of when they think of art, but when I look at a literally well-oiled machine or operation I think it’s a thing of art. So the outsourcing of manufacturing overseas because of cost is a somewhat a slap in the face of those domestic manufacturers.

To be clear I don’t work for a game manufacturer, but rather a heat pump manufacturer. I don’t have any “skin” in this game. But just as generative AI is a threat to artists and writers, so was the industrialization, globalization, and automation revolutions of the last centuries. What we’ve always been told was, “adapt or die”. Or, “if a machine can tighten it better than you, make it faster than you, or drill more holes than you, then let the machine do it and you operate the machine or make the machine.”

Jamey, are there elements I’m missing or not considering?

Frank: Cost is not the primary reason I’ve ever stated. The reason we work with Panda is because we’ve had an incredible experience with them over the last 12 years. I’ve worked with two project managers there (Chris and Shannon), both of whom are excellent communicators and wonderful people. Panda takes responsibility when they mess up (which is rare, but it’s bound to happen in any longstanding partnership). They treat their employees well and pursue environmental sustainability. And they’re able to make all of the products we want (many of which include a number of special components and special versions of standard components that simply aren’t made anywhere else in the world) at scale with consistent quality in reasonable timeframes.

[…] Décidément, le sujet de l’IA est un sujet super, super chaud ! C’est clairement un sujet brûlant qui s’empare, et secoue l’industrie du jeu de société. Quelle pratique, quelle politique avoir autour de l’utilisation de l’intelligence artificielle (IA) dans le processus créatif des jeux de société ? Alors que certains éditeurs ont récemment fait polémique en ayant recours à l’IA pour générer des illustrations, Stonemaier Games, le célèbre éditeur derrière les succès Wingspan, Wyrmspan et Scythe, a pris une position ferme contre cette pratique. […]

The debate around generative image AI often reveals mixed opinions, especially when compared to other forms of AI or non-AI computer tools.

Common Concerns:

* Stealing from Artists

Some argue that generative image AI “steals” because it uses existing work from other artists.

* Financial Impact

Critics claim that it takes money away from artists by producing art without their direct involvement.

* Perceived Laziness

The ease of creating art using AI can lead to accusations of laziness.

* Uninspired Artworks

Skeptics believe that AI-generated art lacks creativity and inspiration.

* Distraction from Other Issues

Some argue that focusing on AI art distracts from addressing other problems in the creative industry.

Counterpoints:

* Text AI vs. Image AI

People seem more accepting of AI when it comes to editing, summarizing, searching, or translating text. Tools like CoPilot, Google, and Grammarly rely on vast text corpora, often without explicit opt-in from contributors. This also takes work away from copywriters, editors, translators and the like.

* Digital Art Editing

AI plays a significant role in editing digital artworks. From suggesting angles during photography to auto-enhancing images in apps like Google Photos, Lightroom, and Photoshop, AI streamlines the creative process. People are much more accepting of this, even though it has “stolen” and been trained on the work of professionals.

* Professional vs. Amateur Results

Automatic editing tools now produce results comparable to professional work, narrowing the gap between experts and amateurs. This directly takes away from professionals.

* Impact on Professionals

However, this progress raises questions about the livelihoods of creative professionals—copywriters, translators, and editors—who dedicate their lives to mastering these skills.

* Enhancing Search Results with AI

That AI will have almost certainly been trained on generic web data – people who had taken hours to meticulously organise their websites/publications. It will also be using the private search terms and results from people who probably didn’t realise they were opting in to their data being used for AI training data. Probably, a lot of this data was mined *before* GDPR and the huge rise in popularity of these AI tools.

It also distracts from the root of the problem – perhaps it is masking a fundemental problem with organisation of the data if it requires AI tools to clean it up for you.

* Improving Ad Results with AI

Gotta spend money to make money, right? It’s a lot cheaper to pay an AI tool to get slightly better results, even if a human would get overall better results – the margin just isn’t there to have a highly qualified advertiser that can only serve one, or a handful of people, compete with an ai tool that can serve billions.

There certainly is a larger discussion to be had here, and we are entering a future where these things exist, whether we like it or not.

To ignore these tools would be foolish, and I think those people would get left behind. Like digital enhancements that have come before, quite often it will be a mix of AI and traditional tools – they are not necessarily at the exclusion of eachother.

But to those who remark about the morality of one tool or another – have you truly considered the use cases for your workflow? Whos pockets you are taking the money from? And where the data used to train those tools came from? (which in some cases, may have been partly you!).

I think all those gray areas you described are fine. They are not replacing human creativity any more than using a calculator hinders solution of math problems. I do very much appreciate your stance on not using AI to generate final art or text. If we all defaulted to using AI art, we are basically saying we will never again have anything truly creative or inspired – just rehashings of what has come before.

I would echo others’ concerns about generative AI, but the one aspect I haven’t seen mentioned directly is quality. Generative AI tends towards mediocrity, which in my mind disqualifies its use in finished work.

I can see why a start-up would need to choose where to put its limited resources into quality, which might lead to using Generative AI, but not an established outfit.

I believe this post won’t age well.

How so?

I’ll take the liberty of expanding on this succinct comment :) Imagine what the world will look like 20 years from now. Maybe some folks choose not to use generative AI, but most likely, there will be many that choose to learn how to harness it. It’ll probably be commonplace at that time to interact with content in many forms that is created for our benefit by generative AI – people will barely give it a second thought (or there may be some qualms – maybe the same as how we interact with cell phones or PCs todays).

If that context turns out to be true – wouldn’t I want to play the newest games that are even more finely tuned to what people enjoy in a game? Wouldn’t I want to take advantage of the lower cost/proliferation of content made possible by gen AI? Now when I’m preparing for my next trip to a Civil War battlefield, I can get a perfect 3-hr game that allows me to simulate the battle ahead of time, instead of just playing a 1hr scenario in BattleCry – or even one that teaches me about the exact spots I’m going to visit on the battlefield. That sounds awesome!

I very much do worry about designers in all this. I’m a software engineering manager, and I can see coding jobs transitioning to integration/publishing jobs as well, and it’s frustrating because coding is fun. I’m sure people will still want to design for a hobby. But with AI we can get so much more design, and potentially better design. As a consumer, while I want to consume responsibility, “more and better” are definitely things I’m looking for.

Thanks Thomas! I appreciate your perspective. As an avid gamer myself, I can relate to “better”, though I’m much more interested in unique/innovative than “more”, and neither of those goals seem to be what current generative AI is pursuing.

We’ll see what the future holds. I’m hopeful that if there are huge advances in AI, it’s focused instead on the types of things humans can’t do well or quickly. For example, figuring out teleportation and FTL travel–we might get there on our own in thousands of years, but if AI could figure it out in a decade instead, I’m all for it. But making art, games, and text? I’m interested in what humans create.

I personally have two things I’d like to see in the usage of AI art, firstly acknowledgement of any image that’s been heavily used in the art by the AI. Secondly just a upfont acknowledgement of where its been used by any companies doing so.

Like many things I think its a tool, but it does need some protection for the original artists work in the form of creditation. On the other hand as a fan who has no ability to create art on my own the doors this opens up for producing fan expansions to work or modifying rules systems to my personal tastes are extremely exciting. I’ve not worked on such projects for a long time but I did a bunch for RPGs in the past and I’d always be reliant on someone else for making it look pretty, which could be bad for me, I’m ADHD so I have periods of hyperfocus I need to complete projects within or I’ll move on to something else, so waiting for someone who is less focused and driven in a tiny space of time will lead to lots of unfinished projects (though I admit layout is my bane, its low dopamine and its the killer of most digital projects I do).

The topic of generative AI in gaming is one that many people have very strong opinions on. I have not really formed a strong opinion either way and think I would lean slightly to the side of being ok with it in many cases. I think during any stage of prototyping whether internally or approaching a company like Stonemaier for a publishing deal it should be ok. I think that if you have labored and planned through many stages of game development and have a prototype you are proud of that is just missing art and you want to add some AI art for showing to a slightly larger tester base or a potential partner go for it. I also agree that some indie single person teams should be ok to use AI art either for crowdfunding the idea to then hire an artist or self publish as is. I think places I would feel icky about it is if an established company like Stonemaier who creates great games on a regular basis and pays amazing artists just decided to stop doing that as a cost cutting measure.

Firstly, it’s important to recognize that the poll’s results may not be an unbiased reflection of general sentiment towards generative AI. Respondents might be influenced by a desire to align with what they perceive as the ethical stance of Stonemaier Games or Jamey Stegmaier himself. This potential bias could skew the responses towards disfavoring generative AI, regardless of its practical or innovative applications in the industry.

[ADMIN: The rest of this comment has been removed, as it directly implies that the topic of the article is about the ethics of AI. The topic of generative AI does have an important ethical angle, but the above article doesn’t mention ethics at all, nor does it dismiss the use of AI for anyone other than Stonemaier Games for ethical or other reasons. This is our stance for us, not for you. If anyone wants to talk about the ethics of AI, you’re welcome to do so elsewhere, as that is not the topic of this article or this discussion.]

Whoops! It looks like my last comment got swallowed up faster than a meeple in a vacuum cleaner. Quick recap before it gets zapped again: Generative AI isn’t just for the big leagues; it’s like the utility player in a game designer’s toolkit—especially useful for the indie underdogs. Just remember, while Stonemaier opts out, for others it might just be the secret sauce they need.

Part of your previous comment is still here–see below.

Yeah you deleted the part in which I challege the ethical stance /moral high ground underlying the article (and yes, there is one).

Be specific.

“Stonemaier Games does not, has not, and will not use any form of AI to replace or augment* creative work. If we’re creating something, we want it built from the ground up by talented people from different backgrounds, perspectives, and cultures, not an algorithm (especially not an algorithm that borrows without permission or at least proper credit from the original artists).”

This part of the article is the moral higher ground, propagating the same idea we have been hearing from a vocal minority of artists on the internet. The notion that generative AI inherently steals from artists by borrowing their work without permission or credit reflects a common misunderstanding of how this technology operates and its potential role in the creative process. Here’s a breakdown of why this view might be considered flawed and how generative AI can indeed serve as a valuable tool for artists:

1. Understanding Generative AI: Generative AI algorithms, such as those used for creating images or music, typically learn from vast datasets that include a variety of sources. These AI models do not copy any single piece of work directly. Instead, they identify patterns, styles, and structures within the data they are trained on and use this learning to generate new, original creations. This process is analogous to how a human artist learns—by studying a range of works and techniques before developing their unique artistic voice.

2. Attribution and Ethics: Concerns about attribution and compensation are valid and highlight the need for clear policies and practices around the use of AI in creative fields. It’s crucial that the datasets used to train AI are ethically sourced and that the creators contributing to these datasets are acknowledged and compensated fairly. This is an area requiring ongoing dialogue and development, aiming to create a sustainable ecosystem that respects and benefits all contributors, including original artists.

3. Augmentation vs. Replacement: It’s important to distinguish between using AI to replace human creativity and using it to augment it. Stonemaier Games’ stance focuses on the idea of not using AI as a replacement for human-driven creative processes. However, generative AI can be used effectively as a tool to augment creative work, helping artists explore new ideas or speeding up parts of the creative process that are more mechanical than conceptual. For instance, AI can quickly generate a variety of design options, leaving more time for artists to focus on refining concepts and injecting personal and cultural nuances that AI is not capable of conceiving on its own.

4. Accessibility and Democratization: Generative AI lowers barriers to entry for many aspiring creators who might lack the resources or specific skills required to fully realize their visions.

5. Innovation and Evolution: Just as photography did not replace painting, but rather expanded the range of artistic expression, generative AI introduces a new medium and set of tools that can lead to unforeseen innovations and transformations in art and design. By exploring AI’s potential, artists and designers can push the boundaries of traditional methods and discover new ways to express ideas and tell stories.

In summary, the view that generative AI steals from artists does not fully capture the complexity of how AI works or its potential to contribute positively to the creative industries. Properly integrated and ethically managed, generative AI can complement human creativity, enhancing the artistic process and broadening the scope of what’s possible in fields like game design and beyond.

Okay! That’s a very small part of the article to focus so much on (it’s so minimal that it’s a parenthetical).

But yes, absolutely, in my opinion, attribution is incredibly important, and I can completely understand why illustrators are frustrated that portions of their work are being used to create composite images. It’s one thing for art to inspire other art, but this is more like 1000 people painting over portions of the Mona Lisa, but you can still see her eyes.

For the most part, I 100% agree with you and I have an ardent stance against the use of generative AI as the primary means of creating content.

However, I take some issue with the “Privilege” point you make. I don’t even support first-time/low budget creators using it, and here is why:

For a long time, I have supported indie, underground and home-brewed art and games, but only when they achieve a remarkable level of quality and demonstrate the real talents of their creators.

I actually believe in the idea that ‘talent’ is a privilege that should elevate certain individuals over others, at least where recognition for their work is concerned. The ability to draw or write well or compose a good piece of music is not universal. I’m a terrible illustrator and I’ve always wished I had that ability. But, because I don’t, I very much value it in the work of others and that is precisely why I pay a premium when I see it done so well.

When creators pull off amazing work in spite of limited resources, shoestring budgets and a lack of options, it’s all the more reason to recognize and support their work. They have overcome a challenge through their own creativity, labor, and problem solving abilities and that is what separates them as a remarkable creator worthy of support.

A creator who relies on gen AI has not shown me that they have any creativity or problem solving skills worth supporting. All they have shown me is that they are comfortable with shortcuts and mediocrity because they believe they should also be successful in a field in which many, many others have devoted far more time, patience and labor and endured through cycles of failure, trial, error and growth.

“Talent” is never merely an expression of one’s ideas. It is an expression of the work one does to bring those ideas into reality.

Well said. It wasn’t that long ago that I had only around $1000 to spend on Viticulture’s art (2012). I found some artists who worked quickly and at a price I could afford. There’s a lot you can afford even on a budget. The size of the illustration, the level of coloring, the number of duplicated features, and whether or not the backgrounds are unique all play into the cost of the art—you can adjust those levers to find something that is visually appealing but also budget friendly. And what’s fair to the artist greatly depends on where the artist is in their career. Instead of approaching a famous Magic the Gathering artist, find someone new who is looking to make a name for themselves. Pay them fairly, of course—exposure is not payment—but you’ll likely find their costs significantly lower than a well-established artist.

What you demonstrated with ‘Viticulture’ (and what put you on my radar back then) was an authorial approach to game design that transcended the budgetary and creative limitations you were working with as a first-time designer.

Because (and I’m not just blowing smoke, I promise), the game certainly did not feel ‘amateur’ or half baked. It felt like a polished product by someone who knew what they were doing. You may not have done the illustrations yourself, but it demonstrated that you knew how to work with and cultivate an approach to the creative direction of the game while working with different artists who may or may not have different skill levels.

As a professional art director, I can tell you that’s everything. Consistency of vision. Knowing how to communicate visually. Aligning many different elements into a cohesive, holistic creative direction. You leveraged the constraints around you into a remarkable finished product.

My fear and belief is that generative AI shortcuts and hotwires this process. It discourages collaboration. It mutes the ability to translate your ideas into visuals through the lens of another artist’s experience and talent. It isolates creators and divorces them from the process of creation. I can’t help but feel the end product of that is not one imbued with the richness of human experience, but rather the emptiness of digital novelty.

The other side of this that doesn’t get talked about as much is copyright. You can not copyright any imagery created with a generative AI program.

Right now, hypothetically, if I wanted to create my own spin-off of Scythe into, say, a tabletop mech-combat game (a la Battletech), I would be unable to take Jakub Rozalski’s artwork and use it for my game. Stonemaier Games and/or Jakub Rozalski would be able to sue me for copyright infringement if it was clear I was straight up pilfering Jakub’s illustrations and repurposing in my own product.

However, You wouldn’t have those protections with generative AI imagery. If you created really awesome illustrations that looked every bit as compelling and original as Jakub’s 1920+ artwork, but did so entirely through Midjourney, I would then be able to take those exact images, put my own IP/ruleset on top of them, and sell it as my own product. There’s nothing you could do to stop me.

This serves as a ‘check’ on publishers and creators and should disincentivize them from using gen AI as a primary means of creation.

As well it should.

I am afraid this is not correct (at least in the US).

Although you are right that in most jurisdictions you cannot protect an image created using AI, you can protect a collection of hundreds of images.

The boardgame (together with the images) create a theme…and that theme can be protected. There is precedent for this (search for Zarya of the Dawn comic).

In any case, this is going into the weeds and I doubt it will ever be the main decision factor of whether or not to use generative AI.

I’m not sure about that.

The Zarya of the Dawn case does make it clear that, while the IP, theme, and text can be copyright and protected, the individual imagery generated by Midjourney can not.

https://www.copyright.gov/docs/zarya-of-the-dawn.pdf

“The new registration will explicitly exclude “artwork generated

by artificial intelligence.” (Page 12, IV Conclusion)

Yes, the overall game or graphic novel could be copyrighted, but an unscrupulous pilferer could just change the IP elements while repurposing the same artwork.

Furthermore, if they manipulated/adjusted the artwork (say, used Photoshop to recolor it with a unique color palette), I don’t see any protections that would give the original ‘artist’ a claim to infringement, because there is no “original artist.”

Awesome!!!!

I think with first time designers without a lot of capital trying to get their design out there (as you note), it could be a way to do that, especially if the intention is to eventually move to paid artists when financially able to do so. That doesn’t mean taking other shortcuts, either, if their passion is the design itself and to be able to get to a place of being able to fully express that with viable art assets from artists. I saw and appreciated that you noted that. Others, I’ve seen be outright dismissive… and I think those attitudes really come from positions of class, of being well off, as if they have no idea what it’s like to be… less well off… and if you can’t afford ‘proper’ artists, you shouldn’t be allowed to make board games. It is true that there are those who will take every shortcut to get through it, but you can usually see that in the quality of the design.

I’ve seen comments from a lot of people on this issue, and I’ve been reluctant to even speak out because of all the outright dismissive, classist attitudes. I appreciate your note on privilege, because a lot of people on this issue don’t seem to recognize their privilege when it comes to this. I’ve seen comments about laziness as well as the questioning general integrity of the design itself.

Hi Jamey,

I agree that for creative work that is monetized I want people to get paid. For rapid prototyping, automating repetitive tasks, etc. I think GenAI is great. I work for an AI company, so I’m obviously biased, but I am convinced GenAI will be ubiquitous in 3 years maybe less. It is inevitable. Trying to avoid using it entirely will be like trying to avoid using anything connected to the Internet. I think the best thing we can do is use it in a responsible and ethical way. It’s the Wild West now, but it will get so much better so quickly that it will be nearly impossible not to use it.

Jason, I think you have some correct observations. I can tell you that on the academic front we are scrambling to keep up with the advances. I fully expect a course on Gen AI to be a core course in our College of Business within two years.

I think there are some many misconceptions about AI. Too many people sees it as a replacement for creative work but it’s really mostly yet another tool in our toolbelt to support the creative work.

I love your games and think a lot of you personally, Jamey, but it’s clear we have a different stance on AI.

I believe in the free market, which has two primary implications in the context of this discussion:

1. I believe you have the God-given right to “take up the pulpit” against AI if you want. I will respect and defend that right even though we disagree.

2. I believe that it’s nonsense, strategically speaking, to fight against technologies which make the value chain more efficient. AI is one of those. In fact, it promises more efficiency gains in the near future than perhaps all other human innovations combined.

Of course, is if an AI model is training illicitly on IP, then we have a moral claim to make. Many models are doing precisely this – and they should be sanctioned – but as an AI software developer, I can confidently say that illicit training is NOT a prerequisite to deliver an accurate, intriguing, “creative” generative model (we’ll leave the philosophical debate about creativity for another time, hence the quotation marks).

Ultimately, I don’t think the market has any moral imperative to “protect” peoples’ jobs. We had no imperative, after all, to protect horse-and-buggy manufacturers when cars were first mass-produced. Those people upskilled, reskilled, or suffered the consequences of their inaction at the dawn of a new paradigm.

And, to address the more pragmatic issue of quality (which I believe is the better argument for your stance): AI isn’t great – yet. Current state-of-the-art models regurgitate patterns. They tend to “average” the training data, making outputs… well, uninspired, to say the least.

BUT (again, drawing on my own expertise building AI), this will soon be an issue of the past. There is research being done which will allow generative models to reason logically from first principles rather than vomiting statistical globs of output. These models will understand both the value of

artistic rules AND the value of breaking those rules – which is one of the few remaining advantages humans have over these systems.

I think humans will always be artistic – it’s fun and fulfilling to create art from your own brain – but that doesn’t mean it will always be a viable “job”.

Best,

Drew

I appreciate you sharing your perspective! I hope it’s clear from my post that I’m speaking of my own lack of interest in generative AI and that Stonemaier is choosing not to go that route–this isn’t me taking a stand about what others should do (there’s no pulpit, I didn’t mention anything about a moral imperative, etc).

Just the opposite of shortsighted — to be shortsighted is to jump into using AI with both feet at this early stage without a second thought of what it costs and what it replaces.

But I saw Jason Tagmire (of Button Shy Games) comment on this thread on Reddit regarding the use of AI-generated art in prototypes, and he had some interesting points that I don’t think I would have thought of on my own (and for which he was subsequently downvoted): https://www.reddit.com/r/boardgames/comments/1c199m0/comment/kz1ygso/

I’d be interested to know your thoughts.

That’s really interesting! He sums up his statement with “I think that using AI art at any stage sets a bad precedent for quality, time, and cost.”

From a publishing perspective, I’m not interested in using AI art for any of our in-progress works. At various stages, our prototypes either have no art (good for testing the strength of a game’s theme) to having concept or final art from the actual artist (to test the functionality of the art and the impact on the experience). The gray area for me is if someone submits a game to us and they want to convey in a few samples how they envision the art or the world of their game. I don’t want them to spend money on art that definitely won’t be used in the final game, so I’m fine with them using any form of temporary placeholder art (ideally not across the entire prototype, but in a few places). If we sign the game, I would remove that art before showing the prototype to the actual artist so it does not impact their creative process.

Just to clarify that discussion on Reddit was a bit unique in that the designer wanted to self publish. They were using AI art early on, then moving onto non-AI art for the final product because they did not agree with it for use in final games. I wanted to explain some issues that could come up in that plan to shift – like the potentially eye opening cost in time and money for non-AI art (both of which are absolutely worth those costs IMO).

At Button Shy we love and cherish our artists. No AI art for us, and we’ve asked for it to be excluded from submissions in support of those artists.

Thanks for clarifying! I’m sorry I missed that context. Like you, at Stonemaier Games we love and cherish our artists.

Several thoughts in these areas:

1) The released AI artwork from Awaken Realms was sloppy, but I also believe using it to create open world games to rival 7th Continent/Citadel or Tainted Grail makes these particular types of games feasible and more replicable to historically reluctant publishers of this genre.

2) There is such thing as a mental inertia when it comes to asking someone to playtest a game. Non-designers in particular need a little extra *something* to get them into the game. Blank cards doesn’t help. AI is particularly helpful when a playtester who’s a designer can look at sticky notes and intentions, whereas a friend or casual gamer can’t see past the scribbles, regardless of the quality of mechanics. In those cases, using something like Wombo hits differently than index cards and sticky notes.

3) Story time: As I was standing in board game row in Target, I overheard someone lamenting how “crap games are filling the shelves…where’s the good stuff? Where’s Monopoly and Sorry?” We’re standing in front of Wingspan and Jaws of the Lion and, you know *the good side of the aisle before Risk and Trouble and Pie in the Face*. And I would bet a month’s paycheck if they were to branch out, they’d buy an AI generated $25 Wingspan knockoff vs. the original.

I listened to a Jake Parker (illustrator/inktober creator) conversation about AI (3 Point Perspective podcast) where he thought it was going. At one point he mentioned people will always prefer and pay a premium for art made by humans; holding something in your hands that you know a human has painstakingly made holds a certain value. I want this to be true, but objectively, as I read about Walmart, Amazon, Apple, and fill in the blank enabling/leveraging child labor to provide lower prices- I can’t help but disagree. People care about their wallets. The lower the price the better, regardless of how it happens. If Wingspan were on the shelf for $25 vs. $45, and the only difference is art by AI vs. (the phenomenal) Natalia Rojas, Ana Maria Martinez Jaramillo, and Beth Sobel *puts Wingspan back on the shelf*- price is the only thing that matters. I’d wager only a handful of people will choose to pay $45. Train an AI on their artwork, reduce their life’s talents into a word prompt, and only a very small demographic will actually care. The only people who really care when it matters about AI are those it affects. To the consumer it “helps” and the artisan it hurts. (“Helps” being subjective. Long-term side effects may include decline in original content and market oversaturation. Consult your doctor before use or if game session lasts 4 hours longer than listed on the box.)

Art is a sunk cost–it does not impact the price of a game, at least not the way we work at Stonemaier Games–our game prices are entirely priced on the per unit landed cost (manufacturing cost plus freight shipping). So using AI art in games would (for most publishers) not impact the price of the game at all.

I can definitely see AI as a benefit in rulebook editing. Quickly identifying contradictions, missing explanations, etc. Or even translating (or at least speeding up the process) to other languages.

Another use case: a friend of mine is tinkering with rulebook specific chat-bots. Instead of searching through the index, just asking the question you have in plain english and having an AI instantly provide the answer. Not just the location of the specific rule, but a contextual reply based on the AI’s understanding of the rulebook as a whole and your specific question.

A third use case: I do think there’s a world that’s not too far away where AI opponents can exist in a (mostly) analog game.

This isn’t something I want to build myself, but I want it to exist, so please, someone steal the idea from me: Multi-modal AI’s have started rolling out (can process different types of information at the same time: image, text, audio, etc.).

You would need some digital tool to interact with (like a smartphone). But I can imagine an AI opponent that can view a game state via a picture of a board (or a constant video feed of a smartphone on some kind of holder), be trained on the rulebook (that perhaps an AI has already edited so you know it’s tight), and communicate what the AI player does in plain english (or any language).

There would be some interesting things to figure out, like different forms of hidden information (hands of cards, points, resources, etc), certain kinds of player interaction like trading. But at a high level, definitely seems possible.

I don’t think this would just be for solo players either. Most games have what players consider to be the “optimal player count.” Having a plug and play extra opponent to fill out 1 or 2 spots in that Twilight Imperium game when you could only wrangle up 3 other people could be pretty nice.

Hi, I have a point of view in which I have been researching and writing a book about AI for the last 9 months. I am also helping a friend create a game. Here is where I have felt the use of generative AI to be useful and ethical in my game creation experiences.

1. Identifying unclear aspects of the rules. It also suggest alternative wordings which we consider.

2. Generate ideas for personal goals. We had a list of 8 personal goals to use in the game. The AI generated about 8 more. Four or five of which had merit. So, it helped spark ideas.

3. Suggest alternative names for the game. It came up with some good games but she liked her original name.

4. Create a Playtest form for the game.

5. Determine the appropriate age-level for the game.

6. Suggest which aspects of the game might be candidates to simplify the game by moving those aspects to an expansion or advanced version.

7. We submitted the game to the Playtest and Win event at Geekway. We used the AI to help revise the sell sheet.

Generative AI can have a place in the creative process but the person using it needs to have content knowledge to assess the responses from the AI. I would be happy to discuss this topic further by email or at Geekway.

Thanks for sharing, Pat! It’s an interesting list and I’m glad you’ve found it useful, but for each entry I can’t help but wonder why? Why use AI to create a playtest form when I could have create the form myself? Why use AI to suggest names when I could brainstorm them with people? And so on.

My simple answer is time and resources. I don’t have a group of playtesters to bounce ideas off of. Most of my time is taken up as a professor and director of an analytics program. I have no financial stake in this game other than helping a friend. So I look to the AI to help me generate useful advice for her to revise her game in the time I have available.

My subplot answer is intellectual curiosity. It is like a toy where, you say, “I wonder what will happen if I try…” Since I am writing a book on AI in Business, I am curious on how well a generative AI can do these things. What will it think of that I don’t? Using an AI on an activity of interest to me adds intrinsic value to using and assessing AI. Insights I gain will be incorporated in my teaching and writing.

I am concerned about the ethical and moral questions surrounding the training data for AIs. Copyright and intellectual property law is not keeping up.

Generative AI is advancing quickly. I saw a demo of a Microsoft product two weeks ago that I think will let you set up an AI whose knowledge set will be limited to your blogs/website.

As an amateur game designer, several of my friends refused to try out one of my designs because it didn’t look nice (I don’t understand that stance but accept it) since then I’ve tried to gussy them up a bit. Usually with free art or pictures I gather from the internet because, this cannot be overstated, I am not an artist.

I have a design I’ve been working on for the last year that I think has potential, the theme is kind of odd and a somewhat original idea, and finding appropriate images that really conveyed what I was leaning into don’t exist. So I turned to generative AI to help sell the idea, and I don’t feel bad about it, I was never going to pay an artist at this stage, and was likely to steal…err borrow…an image anyway.

I do put a disclaimer that the art is AI, for prototype purposes only and not Intended for publication.

As someone who integrates AI tools into my daily work activities. Can you confidently say that the artists you’re paying for illustrations, in no way, use any AI to assist them? Do no illustrators in the board gaming industry use Adobe’s AI tools to assist them in generating ideas or repeat a complex pattern? I’d bed 90% of them do and don’t advertise it, because it truly doesn’t matter. The end state of the illustration is still theirs to own and deliver at a high quality even if the AI helped them generate ideas and/or part of the illustration. Why wouldn’t someone use AI to help them do their job better if it meant more work for them long term?

Terraforming mars even stated it in their interview that they use AI “in conjunction with our internal and external illustrators, graphic designers, and marketers to generate …” and “our use of AI is not to replicate in any way the works of an individual creator”. Simply stating that AI use in an industry is bad for everyone is a pretty harsh/vague stigma.

I highly recommend that individual artists use AI tools in any way they can to come up with and create a quality product. What I am against is replacing an artist with an AI generator (which is unfortunately not the question that was asked).

Contractually, our artists cannot use AI for any illustrations they create for Stonemaier Games projects.

Not for my company either. I also won’t support companies that are choosing to go down that path.

The pitch for “Microsoft copilot” is that it is a copilot – not an autopilot. So if you wanted to ask AI to write your next blog post, for example, the idea is you wouldn’t just generate content and click send. You would use AI to generate the post, then review and edit it into something presentable that works for you. So at the end of the day you could reasonably claim it as “your” content.

There are probably books that could be written on human psychology when it comes to AI. I used it to write a poem just for fun and felt a wierd sense of ownership of the poem as presented, with no changes. After all, it was my prompt that caused the poem to be created. Plus, I know humans are lazy and the majority aren’t going to apply the necessary time and attention that is needed to refine AI generated content into something that is “theirs”.

I probably don’t know enough about AI to even be commenting, but it is going ahead whether we participate or not. There may be business risks either way whether we choose to be a part of it or choose to avoid it. But I fully support Stonemaier’s stance on this one.

This comment generated by AI. Just kidding, it’s all me.

Came here to say the same as Christopher: AI opponents in a digital game are something completely different than generative AI. Whether you are playing against a deck of Automa cards in a solo game or against a computer in a digital game: you are playing against an ARTIFICIAL opponent who will not make random moves but will try to do smart things, hence the name “INTELLIGENT”. It is perfectly okay to call an Automa deck of cards “an A.I. opponent”, even though hundreds and hundreds of human hours went into the creation of that deck. Same with computer opponents: as Christopher said, they are programmed by people who know the game. If you are sending all your mechs in Scythe towards a computer opponent, that opponent should “know” that you are planning to attack it, and it should act upon that knowledge.

This has nothing to do with the generative AI as ChatGPT or the image generators. Those AI systems are black boxes that are trained on thousands and thousands of texts and images from real people. Nobody knows or understands how the GenAI algorithms work, and the output is based on the creative work of others, which makes copyright very shady.

The first form of AI is a form of AI that was crafted with love by real humans, and it’s okay to embrace it. The second form of AI is to be used with caution, because of the copyright mist, and because of the enormous ecological impact of those calculations.

I think you make some good points here, and I want to piggyback onto your point about the difference between AI players and generative AI.

Quoting Jamey above: “Specifically, I was talking about a future where you can feed a near-final prototype into an AI playtest bot and have it spit out 10,000 games’ worth of data in a few minutes. I don’t see this as replacing human playtesters at all, but it could be helpful for identifying circumstantial, niche, and asymmetric imbalances.”

I think any designer should be extremely cautious when attempting to use AI to brute-force playtest a prototype (or even a final version). You could plug in the rules and brute-force it as is, but you would want to make sure you understand the nature of what you’re getting as output. If you don’t make such artificial players truly intelligent, you won’t necessarily find the imbalances you’re looking for. In fact, you might come to incorrect conclusions about balance.

I absolutely believe in the importance of human playtesting a prototype. I also believe equally strongly in the importance of systems analysis of a prototype. I think this might be a more significant gray area in terms of using AI. I’m not an expert, so I’m not sure if any generative AI could replace a human in providing a systems analysis of a board game. But it’s worth keeping an eye on, perhaps.

Interesting points, Alex! As for playtesting: I do believe true AI (the black box model) has a role in playtesting. It will never be able to completely replace human playtesting, because an important part of playtesting is to test the game for fun and experience. A computer can’t tell us how fun a game is. But another important aspect of playtesting is to find the balance for a game. Take Tapestry for example: the asymmetric nature of the game makes for hundreds and hundreds of permutations of civ combinations alone, and if you take the cards into accounts, we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of permutations — impossible to fully playtest manually. If you build a playtesting bot, you can tell that bot to play 10 million games of Tapestry, and to give some statistics. If one civilization won 99,999 of its 100,000 games, you know it needs nerfing.

Now, the problem with programming a bot like that is that you will always program a certain play style into that bot. I’m currently playtesting a game I’m designing myself and I’m using a solo bot to playtest it. This works, but this solo bot plays by the intelligence and the rules I “programmed” in this bot. If a player comes up with a completely new style to play my game, my bot playtesting data is not so useful anymore.

A self-learning AI can figure out all the different play styles itself. Compare the chess computers from the nineties with the current game AIs: IBM’s Deep Blue was a chess computer programmed by people, and it could win through raw power (it was able to see, what was it, 64 turns ahead?), but chess champions could still beat it by playing in an unexpected way. The current game AI models aren’t programmed with strategy. They get the game rules, they start playing the game, they lose over and over again, and they try new things. After 1,000 or 10,000 games, they have figured out winning strategies themselves—strategies nobody thought of. There are examples of AIs doing weird manoeuvres with planes (in flight simulators) that no pilot has thought of, but that are very effective. An AI bot that just gets the rules of Tapestry and then plays 1,000,000 games can give you a lot of useful information. And real people can give a lot of useful information about the game experience.

I’m also in the camp of “generative AI is okay for faster prototyping”

I know it shouldn’t be a big deal but I always feel iffy whenever I show up with handwritten index cards and ask people for their precious time playtesting my game. If I can mitigate this with slightly nicer AI generated images, then I think that’s fine.

I don’t see AI opponents in the same category by default, a good AI is programmed with scripts, environmental conditions, etc. that are unique to your program. Generative AI is not unique, it uses existing examples to output (imo its main “ethical” issue).

Concerning playtesting, if you are doing it on your own game design, your use of generative AI will be limited since the conditions of the playtest will be unique. So in other words, you are going to need to create NEW code to properly playtest with AI. You could perhaps use generative AI for some basic functions depending on your scope/design, i.e. API calls that sort of thing.

I think generative AI could be really useful for prototypes. I have used that in my RPG session build outs. Gets my creative juices flowing. But it could be easy to cross a line after using it for a while.

Thanks for your thoughts on this topic! I agree that AI scripts for digital games are in a different category, but I wanted to be transparent about the gray areas of this topic. :)