If you’re a game designer, I highly recommend Adam Porter’s YouTube channel, Adam in Wales. It has a similar vibe to my game design YouTube channel in terms of its focus on specific game mechanisms, but Adam is far more eloquent and polished.

Adam has a series of videos about what he’s learned over 10 years of game design, and he recently posted his top 10 insights. I think they’re worth sharing and discussing. The parts in bold are Adam’s titles for each section of the video:

10. You define success for yourself: I spoke to a designer earlier this year about their unpublished game, and this person had become fixated on their game winning the Kennerspiel des Jahres (a big German award) because people in the industry kept telling them that was the future of this game. These industry insiders were setting a completely unrealistic framework of success for this new designer, and I encouraged them to instead define their own success, just as Adam does in his video. I prefer frameworks of success that I actually have control over: For example, success can be getting a prototype to the table or following through on a game to completion (opposed to defining success based on awards, sales, or even publication). I discuss this in more detail in my recent post about creating something meaningful to you in 2024.

9. Don’t make the game which you want to play: This is a tough-love insight from Adam, who admits that his quirky taste in games doesn’t always align with marketability. In a way, he’s saying that if the goal of your game design pursuits is to publish your game and have other people actually play it, design a game for that audience, not for necessarily yourself. At the same time, I would add “design a game that you want to playtest” and “design a game you want teach“. I’ve found that I end up doing both of those things far more than I get to play the final version of my game for enjoyment.

8. Make Sell Sheets: As a publisher who accepts rolling submissions, sell sheets are incredibly helpful! The best sell sheets distill a game down to the most important things a publisher needs to determine (a) if the game is a good fit for them and (b) if the game is intriguing. Making a sell sheet is also a great exercise for figuring out how to describe your game to anyone in just a few sentences.

7. Be willing to change theme: Adam talks about this mostly in the context of being flexible if a publisher is interested in your game but believes in a more marketable, appealing, or accessible theme. I agree, though it’s also nice when a theme or world is designed so well into a game that the mechanisms make sense because of the theme. I’d also add that a willingness to adjust the theme is a handy tool in general–not just to appease publishers–as you might discover that the theme you started with isn’t as good of a match as another theme you discover during the design journey.

6. Publishers depend on partners and distributors: I really like what Adam says here. He describes that publishers don’t work in a vacuum: You might hear from a publisher who is very interested in your game, but after they get feedback from localization partners, distributors, or advisors, they may decide that there isn’t enough interest in the game to pursue it (or the feedback may reinforce or enhance their original decision). This is why we continually ask blind playtesters to rate our in-progress games: If a game’s ratings aren’t improving over multiple waves of playtesting, we may have to make the difficult decision not to proceed with the game.

5. If your game is rejected by everyone, don’t self publish: I think this is one of the most important insights Adam shares. He’s not saying that people shouldn’t self publish; rather, he’s saying that if a number of people who generally love games specifically do not like your game, self publishing isn’t going to fix that issue. Adam closes this point by saying, “Self publish because you want to self publish, not because you can’t find a publisher.” If you’re excited to run a business, go for it! But do so with a product that people are really excited about.

4. Some games are hard to sell: Adam talks about how sports-themed games and abstract games are generally difficult to get publishers excited about. Those are just two examples; if you pitch enough games to publishers, eventually you’ll probably find a few genres that are consistently rejected for a variety of reasons (e.g., they don’t sell, there are too many similar games, etc). I think it’s important to be aware of what sells and what doesn’t (look at the number of ratings on BoardGameGeek); it’s also humbling to admit to yourself that your game probably won’t be the exception. I don’t think this should stop anyone from working on games in genres that don’t generally get a lot of love from consumers, as otherwise games like Wingspan wouldn’t exist.

3. Never search the discard pile: I could give Adam a hug for saying this (which he further expands to include deck and other players’ tableaus). This isn’t abstract advice: Adam is specifically saying that if your game has a deck or discard pile, do not give players the ability to look through the deck, discard, or opposing tableau to gain/use a card they select. It brings the game to a halt, potentially for a significant amount of time. There are rare exceptions to this, but usually you can offer a similar benefit in a way that is much more considerate of other players (i.e., shuffle the discard pile, draw 3 cards, then select 1). In a more general sense, I try to be aware of–and avoid–abilities and powers that change a quick simple turn into a long complicated turn.

2. Do not pay for placeholder art: Adam is speaking directly to designers who don’t want to self-publish. The publisher is responsible for the art. If you have strong feelings about the art as a designer, that’s great–please share them with the publisher. But if you pay for the art or spend your time creating the art, most likely you’ve just wasted time and money, as the publisher will almost certainly commission a different artist for the game.

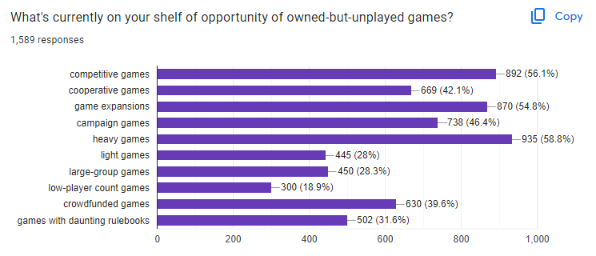

1. Accessibility trumps just about everything else: I love that Adam ends this list with the concept of accessibility. This is a big topic, but I distill it down to this: I want to do everything in my power to make our games easy to get to the table. This starts with the price and extends to the moment you open the box, try to learn the game, teach the game, and remember the game after not playing it for a while. This isn’t limited to simple games: There are many complex games where the designer and publisher have gone above and beyond to create an intuitive user interface, amazing tutorials and rulebooks, and removing all exceptions and tiny rules that players need to remember. Every now and then I look at my shelf of opportunity of unplayed games (or the games on my shelf that I played once and haven’t played again in months) and ask myself what it is about those games that has made them difficult to get to the table. In fact, it’s something I asked in our recent demographic survey:

Huge thanks to Adam for inspiring this article and adding value to other designers, and I hope this gave you some good food for thought. Let me know your observations and questions below, and I recommend checking out the full video:

***

Also read:

- My Thoughts on Pam Walls’ “6 Truths About the Board Game Industry” Video

- 4 Steps to Pitch Your Game to a Tabletop Publisher

If you gain value from the 100 articles Jamey publishes on this blog each year, please consider championing this content! You can also listen to posts like this in the audio version of the blog.

11 Comments on “My Thoughts on Adam Porter’s “Decade of Game Design Wisdom” Video”

Leave a Comment

If you ask a question about a specific card or ability, please type the exact text in your comment to help facilitate a speedy and precise answer.

Your comment may take a few minutes to publish. Antagonistic, rude, or degrading comments will be removed. Thank you.

Jamey, I’ve seen several of Adam’s videos as they’ve entered my feed for one reason or another…I consume a lot of content as I have a 30-45 min commute (each way) to work every day. I really liked the distilled list as I often advise my designer-clients with the following ABCs ~ A: Accessibility, if this is your first design, don’t go crazy making it too difficult, because it will inevitably be “too much.” B: Budget, make sure you’re reasonable in your approach with regard to art and prototypes, take care of those who playtest your game and edit/proofread your rules; and C: Change Agent, you, as a designer, must be willing to make change and not be tied to a specific mechanic or thematic idea.

I like those ABCs, Joe!

#9. I feel that it’s nearly impossible to innovate if you’re giving people what they want or expect. Mark Rubin has a lot to say about this if you consider design to be art. It’s good business advice, but not necessarily good for making something proprietary and memorable. My 2 cents.

#1. What a hard-earned lesson this one is. It’s on point and something worth striving for every time.

Perhaps I’m hearing/reading something differently than you, Mark, but I’m not seeing the advice to give people “what they want or expect.” What I’m hearing from Adam is that if you’re making a game for other people to play (not just something for yourself and no one else), keep those people in mind as you create the game. It’s an act of selflessness and awareness of others, not a recommendation to do something rote, boring, or that already exists. I’ve seen you accomplish this with your games: From an outside perspective, it seems that you’ve found a great balance between making games that are meaningful to you while putting the experience of the players first.

Ah. I see that perspective, too. Thank you for the reply. We all have so much to learn from each other.

Number 1 I can relate to. I have so many games that we do not play simply because I dread the amount of time and effort needed to set up the game. I wish graphic and box designers had that in mind when designing boxes, boards, trays and components so that they tried to design in a way that storing the game would help with the next gaming session.

Last year I decided that would be the main decision point when purchasing new games. If setting the game up for play takes more than 5 minutes, even knowing the rules and having played several times before, I do not buy.

I rather pay a premium for a game I will play than a reduced price for something I won’t bring out.

I hear you! My target for setup time for our games is 5 minutes, plus at most 5 minutes of rules overview for teaching new players before they can start taking turns.

Ironically, we reached this decision being forced to play simpler games with our kids. Then, we realized that 25 minutes to set up an entertaining evening was not required. We could be playing Splendor or Century Golem in 2 minutes. And those were damn fine games. We starting playing complex games less and less and now we barely miss them.

Agreed. There is a game that once got a lot of playtime in my family. We then borrowed an expansion for the game and never even set it up once because we just remembered how long it took to put it all together (and separate it all at the end too). We probably should have just done it, but its all about minimizing the steps that gets you onto the table (thinking how app designers do the same thing, minimizing the steps and difficulty for you to get on their app and get scrolling or buying…etc)

Jamey I’m curious how #7 game theme changes might work. Will publishers reject a game solely on the theme? Or will they generally look past the theme (momentarily) to check for the games potential, and then suggest a retheme if they think the game could go somewhere? How detrimental can the theme be to what might otherwise be a good game?

Andrew: If a game has a great mechanical hook but the original theme doesn’t excite the publisher, I think they’re generally still likely to learn more about the game and ask the designer if they’re open to a retheme. But a well-selected theme can definitely help the publisher envision the potential for the game, so the converse is also true: If it’s viewed as a boring, overdone, or generic theme, it could be a detriment to the pitch.